The Hall of Fame career of Dr. Bill Vega

Mike Muñoz hesitated when he was first asked to become interim superintendent-president of Long Beach City College in early 2021. The college had just experienced several top leadership transitions, and Muñoz wondered how things would be any more stable for him.

Muñoz did what he always did when presented with opportunities to promote: he consulted Dr. Bill Vega, a personal and professional mentor since his days as a Cal State Long Beach doctoral student.

“It’s going to be different because it’s you,” Vega said, going on to describe Muñoz’s talent for engaging people and avoiding common leadership mistakes. “I believe in you.”

Muñoz accepted the temporary appointment, which later turned permanent.

“He was right,” Muñoz said. “The position fit like a glove.”

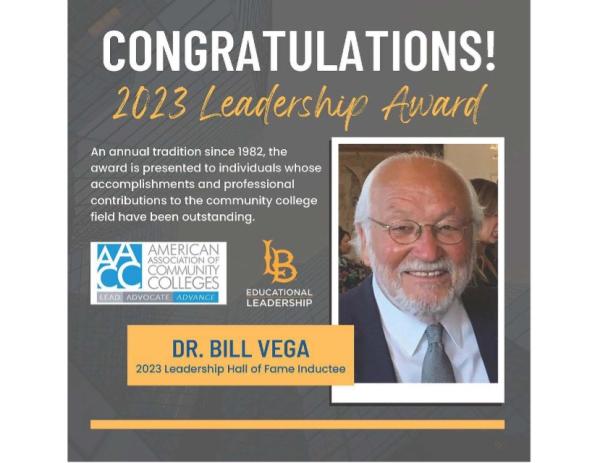

Vega has helped guide and elevate the careers of hundreds, possibly thousands of educators throughout Southern California as a professor, dean, president, chancellor and now distinguished faculty in residence at Cal State Long Beach.

For that he was inducted into the American Association of Community Colleges’ Leadership Hall of Fame April 1. Vega has spent most of his career in the community college system including as president of Coastline Community College and chancellor of the three-campus Coast Community College District.

The Hall of Fame honors “individuals whose accomplishments and professional contributions to the community college field have been outstanding.” Vega is one of 10 people being inducted.

It’s not just Vega’s vast experience and exceptional longevity that make him outstanding, students and colleagues say. It’s also his warmth, generosity and humility.

Muñoz saw it when he came out of the closet and Vega stepped in as a role model when his own father rejected him. Paul de Dios, another former student, saw it when his wife died of an aneurysm and Vega regularly checked in on him and his two boys.

“He’s an important person in a lot of people’s lives,” said de Dios, now vice president of student services at Cypress College. “I’m glad that he’s being recognized.”

ROOTS OF HIS SUCCESS

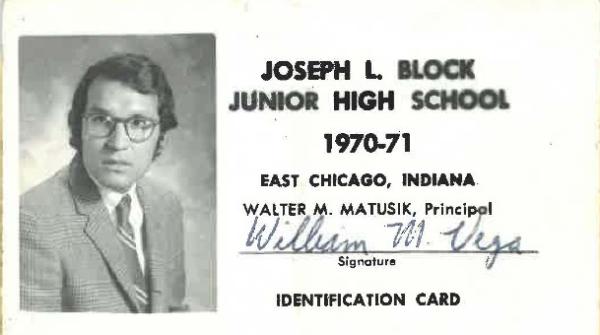

Vega’s career was first shaped in the northern Indiana steel town of East Chicago where he grew up.

The steel mills attracted workers from all around the world. Vega estimates more than 30 ethnic groups were represented in his high school class and that most classmates spoke another language at home including Spanish, Greek, Romanian, Polish and Croatian.

The teachers were brilliant and went above and beyond, such as the math teacher who came to school early to teach her pupils calculus since the official curriculum stopped at trigonometry.

From them Vega learned to relate to and appreciate people from all walks of life, and that the primary focus of educators should be doing what’s best for students.

“So many of us became educators, and I’d like to think that’s because the teachers we had were just the best,” Vega said of his classmates. “…I credit so much of my success to them.”

The language Vega spoke at home was Spanish. His father immigrated to East Chicago from Mexico and rose from laborer to foreman in the steel mills. His mother moved there from Texas and was a stay-at-home mom to Vega and his eight siblings.

“I have seven sisters and one brother, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” Vega said. “It was a wonderful childhood.”

Five of Vega’s paternal uncles fought in World War II, and during poker games after the war shared their stories. So when Vega graduated from Indiana University, Bloomington with a management degree in 1967, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was sent into the raging Vietnam War.

Vega served as a machine gunner in South Vietnam for four or five months and then as a squad leader for four or five more in the Mobile Riverine Force.

“We’d get onto carriers going down the Mekong River, get dropped off, conduct (search and destroy) missions for three or four or five days, and then get picked up,” he said. “We’d come back to the ship, clean our weapons, stay there for a day or two, and then do it all over again.”

Vega earned the Air Medal for conducting at least 25 combat assaults by helicopter while receiving fire and the Bronze Star for the months he was a squad leader during heavy combat. He’s proud that none of his men were killed.

“What I learned there is that nothing’s more important to us than our family and friends,” Vega said. “And I’ve always made that a priority in my life.”

What he also learned, while helping fellow soldiers improve their reading, is that he had a knack for teaching.

TEACHING AT HOME AND ABROAD

Vega’s first teaching job was in the math and history department in East Chicago Public Schools. A year into it he flew to Germany to see a friend and learned the University of Maryland, which offers classes at U.S. military bases around the world, was looking for economics teachers.

Vega, who earned a master’s degree in economics and business from Appalachian State University in 1970, taught economics for the University of Maryland throughout Europe. That included in Spain, Holland and finally Germany, where the highlight was meeting his now wife, Karin, on a blind date.

Bill and Karin Vega have been married for 50 years this December, and have two children, Bill and Daniele.

Vega always wanted to come to California, and in 1974 did so to teach in the Economics Department at Los Angeles City College. He quickly joined the administrative ranks by becoming the college’s director of outreach.

In the years that followed, Vega was associate dean of instruction at Contra Costa College in San Pablo, vice president of academic affairs at Compton Community College and dean of curriculum and instruction at El Camino College in Torrance.

Between 1985 and 1993, Vega served as president of Coastline Community College in Fountain Valley. In late 1993 he rose to chancellor of the three-college Coast Community College District based in Costa Mesa.

Vega is most proud that during his tenure as chancellor, the three campuses’ leaders became much more collaborative and collegial, faculty grievances dropped by half, and voters approved Orange County’s first general obligation bond for community college construction projects.

During almost all his years in administration, Vega continued to teach.

“I felt it was important for me as an administrator to continue to have the classroom experience and continue to have that direct interaction with students,” he said.

It’s rare for a person of color to become a community college chancellor, said longtime friend and colleague Jerry Hunter, retired chancellor of the North Orange County Community College District.

It’s challenging to convince the “Noah’s Ark” committees of 17 to 18 people of different constituencies that you can perform the job and be true to yourself, said Hunter, who is Black.

“That in and of itself, from my perspective and experience, speaks to him as an individual, his level of preparation and his ability to convince people that he’s capable of providing leadership at the highest level,” Hunter said. “That’s something not to be taken for granted.”

The length of Vega’s tenure, 11 years, far exceeds the norm of three to five years, Hunter said. It’s a testament to not only his integrity and commitment to students but good political instincts given his bosses were often power-driven elected officials.

He knew when to fight and when not to, how to win over a majority, and how to maintain an “ethical north,” Hunter said.

“He had some challenges with one board member in particular but he worked his way through that,” Hunter said. “And he was true to himself, and that’s the trick.”

When Vega retired as chancellor in 2004, he was recruited to take on the presidency of Dubai Men’s College, where he enjoyed learning a new culture and new customs.

Three years later he returned to Southern California and began teaching at Cal State Long Beach as distinguished faculty in residence, a title the College of Education grants to those who’ve had full, high-level careers before joining its Educational Leadership doctoral program.

Today Vega teaches an introduction to community college course and a fieldwork class through which students get placed in internships. He also recruits students for the doctoral program and teaches two doctoral classes.

“I enjoy counseling and mentoring a lot of the students and helping them in their long-term career upward mobility,” he said. “I still know a lot of folks in the community college field, and I like to help our students get their start.”

While Vega’s resume is impressive, it’s those stories of students he’s mentored that best illustrate Vega’s impact on the local educational landscape.

UPLIFTING THE FIRST GENERATION

Muñoz, the Long Beach City College superintendent-president, had no higher aspirations than dean after earning his doctorate from Cal State Long Beach in 2010. He certainly didn’t want to become a young president.

But Vega saw talent, leadership skills and ability in Muñoz that Muñoz didn’t see in himself.

“’No, you’re going to be a president,” Vega told him. “And you need to be one sooner than later.”

Every semester, Vega sent Muñoz a text or email arranging lunch at Chili’s to see how he was doing. It meant a lot that Vega initiated those meetings, Muñoz said, because “you don’t want to feel like you’re chasing people down” for help.

And Muñoz needed the help, he said.

“We have to remind ourselves that first-generation college students grow up to be first-generation professionals,” Muñoz said. “We don’t always have the social and cultural capital to be able to go to other folks in our family, in our networks, to guide us, to teach us about the hidden rules behind these processes and how to navigate these spaces.”

De Dios, the now-Cypress College vice president, said he thought he knew everything about student services when, after three years of cajoling by Vega, he started the doctoral program at Cal State Long Beach. Vega showed him he was wrong.

“He was like, ‘Man, there’s so much more than just giving services,’” de Dios recalled. “There was the relational piece of management, there’s the vision development, there’s the equity work that is so important. He really was instrumental in giving me a 30,000-feet view of education, because I was really a practitioner.”

De Dios also learned from Vega the importance of really getting to know faculty and staff, treating employees not as employees but as human beings, and to always put students first.

And like with Muñoz, Vega convinced him he could make a bigger impact as a vice president or president, and it pushed him to aspire to higher-ranked positions.

“When you don’t think you can do something he’ll say, ‘Why not?’” de Dios said. “He’s the cheerleader, he’s the role model, he’s the mentor to, I would say, thousands of people.”

At Cal State Long Beach, Vega is known for always being available and serving as a “guiding spirit” to both students and faculty, said Dr. Don Haviland, chair of the Educational Leadership Department.

Before the pandemic, Haviland would regularly see Vega on campus on Fridays and Saturdays — when not a lot of others are around — because that’s when students could meet. And Vega uses his vast and deep connections to help students reach their career goals, Haviland said.

“He knows everybody in the L.A. basin, he’s had a long and successful career, so he can help students really think about what they want to do professionally and then connect them with people who will help them succeed in that way,” Haviland said.

And Vega plays an important leadership role among faculty that “I don’t know we think about or articulate enough,” Haviland said. He’s been known to help junior faculty members sort out problems or suggest ways to approach sensitive situations.

“He’s leaving a legacy,” Haviland said of Vega’s long career. “It’s literally hundreds, maybe thousands of students who have some sort of imprint from his experience and insight. It’s just fantastic.”