PK-3CP: A Guide to Student Success

The PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program (PK-3CP)

A Guide to Student Success

Ruth Piker, Ph.D., Program Coordinator

Georgina Ramirez, M.A., PK-3 ECE Advisor

Georgina.Ogaz@csulb.edu, EED-53

Welcome to CSULB’S PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program (PK3CP) Guide to Student Success Handbook! This handbook was prepared for PK-3 teacher candidates at California State University, Long Beach. We hope you find it helpful to complete your PK-3CP successfully!

Department of Teacher Education, College of Education

California State University, Long Beach

Section 1: College of Education

Vision: Leaders in Advancing Equity & Urban Education

Commitment Statement

CSULB’s College of Education is committed to advancing equity and urban education by enacting racial and social justice. We illuminate sources of knowledge and truths through our intersectional scholarship, pedagogy, and practice. We collaborate with and are responsive to historically marginalized communities. We cultivate critical and innovative educators, counselors, leaders, and life-long learners to transform urban education, locally and globally.

Section 2: Summary of CTC Credential Requirements

As per the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC), the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential requires the applicant to have completed all of the following requirements:

- Possession of a bachelor's degree or higher from a regionally accredited institution of higher education.

- Completion of the subject matter requirement.

- Completion of a Commission approved PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential preparation program.

- Passage of Commission approved Teaching Performance Assessment.

- Passage of the Foundations in Literacy or a Commission approved literacy assessment aligned with the requirements of Education Code section 44320.3.

Section 3: PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential Program

This proposed program aims to prepare candidates to earn the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. Through this program, candidates will develop the skills and knowledge necessary to master the Teaching Performance Expectations (TPE) of the PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential, which will prepare them to successfully teach in PK-3 educational settings and pass the state-mandated Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA). A PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential teacher is authorized to teach preschool, transitional kindergarten, kindergarten, first grade, second grade, and third grade in self-contained classrooms.

This credential program aims to cultivate diverse educators who utilize evidence-based practices to create developmentally and culturally responsive curricula and assessment strategies for children from preschool to third grade. The program's courses focus on the sociocultural constructivist approach to pedagogy and practice. Teacher candidates are expected to nurture and prepare all children in the classroom with an equity-minded perspective. They develop a deeper understanding of the diverse families in urban settings and apply this enhanced understanding to the curriculum and their interactions with families. Coursework can be pursued on a full-time or part-time basis.

The PK-3 program is a traditional Post-Bachelor credential program that can be completed in three semesters. Candidates enrolled in the program complete 45 units of coursework and over 600 hours of required clinical practice experience. The PK-3 credential program recognizes and grants clinical practice equivalency for prior knowledge. More information can be found in the PK-3CP Clinical Practice Equivalencies website. We support our candidates by offering courses in the evenings and on Saturdays and help prepare them to pass the PK-3 Literacy Performance Assessment and Math Performance Assessment.

The program prepares candidates for mastery of the PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential's Teaching Performance Expectations (TPE). At the conclusion of this program, students are prepared to successfully pass the Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA) by completing courses that equip them with knowledge and skills to:

- Identify, organize, and implement a developmentally appropriate core curriculum for ALL children’s learning in the subjects of literacy, mathematics, health, and science in PK-3 settings;

- Create and maintain effective environments that are diverse, equitable, and inclusive of multilingual learners and children with disabilities or other special learning needs;

- Monitor, support, assess, and document children’s development and learning through clinical practice opportunities;

- Articulate the importance of taking an asset-based approach and build on children’s individual strengths and levels of growth and development, and

- Develop as a professional early childhood educator.

Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs)

The purpose of the Teaching Performance Expectations (TPE) is to provide candidates with performance-oriented knowledge, skills, and abilities expected of a beginning PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential candidate at the point of initial state licensure (CTC). The TPEs were intentionally developed and adopted by the Commission to be broadly encompassing and descriptive of the continuum of teaching and learning across all educational contexts. They have been adapted specifically for the PK-3 context and grade levels, purposefully reoriented to reflect developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood classrooms (CTC).

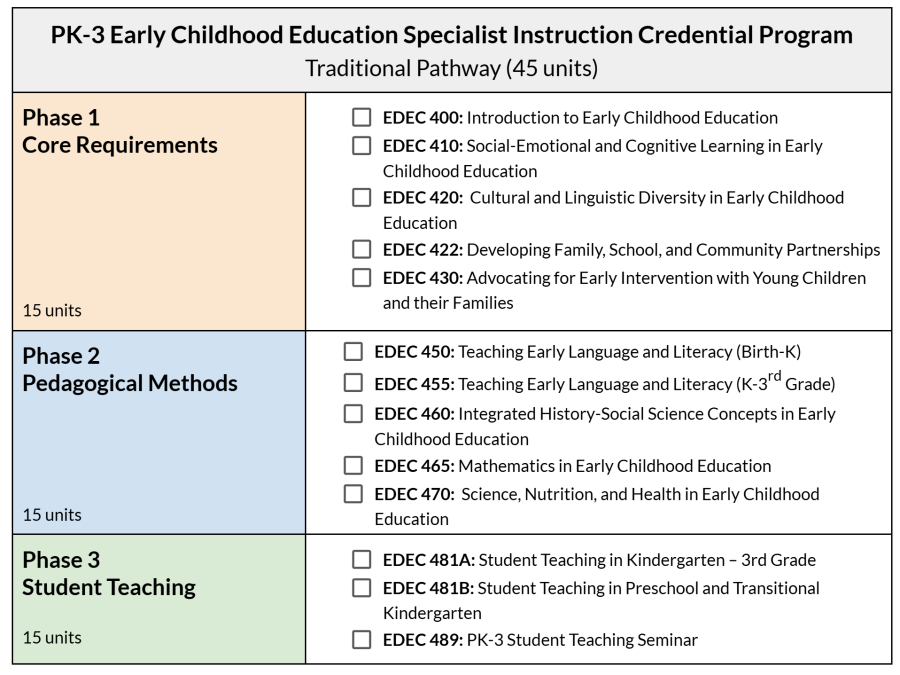

The PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program consists of 45 units. The coursework features a structured, sequential, and spiraled curriculum divided into three phases. Courses must be completed in the order of Phase 1 Core Requirements, Phase 2 Pedagogical Methods, and Phase 3 Student Teaching. Candidates cannot progress to the next phase without completing all courses from the previous phase. A grade of “C” or better must be earned in non-pedagogy courses, and candidates must maintain a 3.0 grade point average in all pedagogical method courses. Candidates seeking additional subject-specific content support, such as in math or science, will receive a list of recommended content courses.

All courses are offered in hybrid formats, including in-person, online synchronous, and asynchronous modalities. Candidates may choose to complete the program as a full-time or part-time student.

Phase 1 Core Requirements

In Phase 1, teacher candidates are introduced to early childhood education (ECE) to gain a broader understanding of early childhood development and learning, with a special emphasis on the sociocultural constructivist approach to pedagogy and practice. They also develop a deeper appreciation for the diversity of families in urban settings and apply that understanding to the curriculum and their interactions with families. Candidates examine concepts such as culture, educational equity, social justice, multiple forms of diversity, and social-emotional development and learning. They recognize how children’s cultural, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds can serve as resources for creating inclusive classrooms. Each candidate completes five courses requiring clinical practice experiences in classroom settings to earn at least 70 hours of clinical practice.

Phase 2 Pedagogical Methods

In Phase 2, teacher candidates are given opportunities to connect theory and practice in pedagogical strategies specific to their subject disciplines. Candidates take five pedagogy classes focusing on literacy learning and teaching, history-social studies, mathematics, and science and nutrition. To be eligible for Student Teaching, candidates must complete all five subject-specific pedagogy courses with a grade of "B” or better.

Phase 3 Student Teaching

During student teaching, teacher candidates engage in progressively complex clinical practice experiences in PK-3 classrooms under the guidance and support of early childhood education cooperating teachers and university mentors. Candidates complete their student teaching experiences in K-3rd grade and preschool and transitional kindergarten classrooms. The program includes a student teaching seminar course to assist candidates with submitting documentation for the PK-3 LPA and MPA. Candidates must apply to become student teachers in the semester before starting their student teaching. Candidates who have received clinical practice equivalency for prior experience may be eligible to waive student teaching in preschool and transitional kindergarten classrooms. More information can be found in the PK-3CP Clinical Practice Equivalencies website.

Clinical practice in the PK-3C program is integrated throughout the program's duration. Teacher candidates undertake coursework across various domains, topics, and issues in early childhood education. Each course mandates candidates to complete a minimum of 10 hours of clinical practice. The clinical practice is closely aligned with the course content. Candidates learn about various topics and then reflect critically on the connection between classroom coursework and real-world teaching experiences through their clinical practice. Comprehensive assessment and supervision during clinical practice are hallmarks of the credential program.

The three phases of clinical practice align with the program’s three-phase course sequence. Cooperating teachers provide an evaluation and certification that the candidate has completed the required clinical practice hours, and faculty verify the completion of the necessary field assignments. Throughout the PK-3C program, candidates will complete 655 hours of clinical practice.

Clinical Practice | Course Sequence | Clinical Practice Hours |

Clinical Practice 1 – Early Clinical Practice | Phase 1: Core Requirements | 80 |

Clinical Practice 2 – Pre-Student Teaching | Phase 2: Pedagogical Methods | 50 |

Clinical Practice 3 – Student Teaching | Phase 3: Student Teaching | 535 |

- Clinical Practice 1: Early Clinical Practice

In the early clinical practice phase, candidates complete 15 units of core requirement courses, including 80 hours of observations or small-group lessons in PK-3 classrooms. Thus, candidates complete a total of 80 hours of clinical practice.

- Clinical Practice 2: Pre-Student Teaching

Candidates must complete 15 required units of professional preparation courses, which encompass 50 hours of small-group and full-class lessons in PK-3 classrooms. They are also required to finish at least 12 units of professional preparation courses, including three units focused on effective methods for teaching English Language Skills, to be eligible for advancement to student teaching. One 3-unit professional preparation course may be completed during Clinical 3 - Student Teaching. Additionally, candidates participate in up to 50 hours of clinical practice.

- Clinical Practice 3: Student Teaching

Candidates complete 12 units of professional preparation or Student Teaching within one semester. They spend 3/5 of the semester in a K-3 classroom, which amounts to 315 hours of clinical practice, and 2/5 of the semester in a preschool or transitional kindergarten classroom, totaling 210 hours of clinical practice. Overall, candidates complete 525 hours of clinical practice.

Reporting Clinical Practice Hours

Candidates must report all clinical practice hours on their MyCED account. In MyCED, candidates provide the name of the school, logged hours, and the status of hours completed. Please review the MyCED Logging Hours Guide to learn how to report your clinical practice hours. If you need assistance navigating MyCED, please visit the College of Education MyCED for Initial Teaching Credential Students website.

Student teaching is the culminating clinical practice experience in the PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential Program. It occurs in the final semester of the program, where PK-3C Program candidates apply and integrate the pedagogy they have learned in their other coursework into actual classroom experiences. For some candidates, student teaching is a full-time commitment, spanning five days a week for the duration of the university semester. Candidates may be placed in public school TK-3 classrooms and public preschool classrooms.

Student teaching consists of two six-unit sections: EDEC 481A, Student Teaching in Kindergarten–3rd Grade, and EDEC 481B, Student Teaching in Preschool and TK. The student teaching semester also includes the course EDEC 489, PK-3 Student Teaching Seminar, which guides and prepares students for the Cal TPA assessment. Student teaching takes place in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms. The Student Teaching Orientation is typically held in the week preceding the semester's start, with assignments generally beginning during the first week of the semester. The Student Teacher Handbook contains additional details and requirements.

Section 4: Admissions to the Program

Candidates must apply to both the University and the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program (PK3CP). Candidates typically begin by applying for admission to the university for conditional acceptance to pursue the PK-3CP.

Once the university application is completed, Candidates must submit the PK-3 Credential Program Application. Candidates may use the PK-3CP Admissions Requirements Checklist to ensure they have met all the program admissions requirements to be eligible for admission to the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program. A complete credential program application must be submitted online at MyCED. The PK-3CP application and instructions for submitting are available on the program admissions website under Submitting Program Application.

Student Teaching is the culminating field experience in the PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential Program. It is completed during the final semester(s) of the program where PK-3C Program candidates apply and integrate the pedagogy they have learned in their other course work to actual classroom experience. For some candidates, student teaching is a full-time five days per week experience for the length of the university semester. Candidates may be placed in public school TK-3 classrooms and public preschool classrooms.

Candidates complete a student teaching application and submit it online at MyCED. Candidates complete all required coursework, with an option to enroll in one pedagogy course with student teaching. Candidates must submit all their Self-Evaluation Disposition Survey from each semester and cooperating teacher evaluations from Clinical Practice I and II.

Section 5: Candidate Evaluations

Early childhood represents a unique stage of development and learning that markedly differs from that of older children and various grade levels. As such, young children need educators who are compassionate, caring, committed, and respectful toward both the children in their care and their families. We expect PK-3 teachers to cultivate partnerships with the children’s families and actively engage all children, regardless of age, background, or individual ways of being. The PK-3 credential program seeks candidates who will offer their students a sense of belonging and security, engaging and exploratory instruction while building strong connections and partnerships with families and the community. To ensure that all candidates meet these professional qualifications upon completing the program, they are assessed throughout their studies by course instructors, cooperating teachers, and university mentors. We expect all candidates to be reflective practitioners. Therefore, candidates will complete a disposition survey at the end of each semester to self-reflect on their professional performance in each class and their interactions with instructors and teacher mentors. The evaluation forms can be found on the PK-3CP website, under the Documents and Forms tab.

Candidates who struggle to achieve at least proficiency or an acceptable level of teaching and professionalism during each evaluation will meet with the program coordinator. The program coordinator and the candidate will review the evaluation results and create a plan to help the candidate meet the program expectations. However, if the candidate cannot meet these expectations, they may be removed from the program. Candidates can find more information in Section 6 of this Guide.

Candidates should practice and demonstrate professional dispositions during all meetings and interactions with instructors, peers, and staff during the program. Developing as a Professional Early Childhood Educator is a Domain for the Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs). Therefore, program instructors evaluate each candidate on five criteria, including complying with classroom policies and respecting and demonstrating professional interpersonal skills towards peers and instructors.

In Clinical Practice I and II, cooperating teachers play a vital role in shaping the development of candidates. They offer guidance, support, and constructive feedback throughout the clinical practice experience. As part of this process, cooperating teachers must complete evaluations for each class and hour of clinical practice.

The evaluations serve as a formal record of the candidates’ progress and areas for growth. They provide essential insights for both the candidate and program administrators, helping to ensure that the candidate meets the profession's standards and expectations.

All candidates must complete a disposition survey at the end of each semester. This survey serves several purposes. First, it allows students to reflect on their behavior, attitudes, and professional dispositions, giving them a chance for self-assessment. Second, feedback collected from these surveys helps instructors and program administrators identify strengths and areas needing improvement within the program.

The survey generally includes questions regarding students' commitment to their studies, interactions with peers and faculty, adherence to ethical standards, and overall professional conduct. By collecting this information, the institution can ensure that students cultivate the essential skills and attitudes needed to become effective educators.

Section 6: Student Academic Support and Resources

The PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program provides candidates with information regarding how to access and guide their success in meeting program requirements. Upon admission to the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential Program, candidates participate in an orientation meeting covering program requirements, state credential requirements, professional examinations, and student teaching expectations.

Candidate progress in meeting competencies is monitored through a combination of faculty advisement, evaluation tools, and self-monitoring. Faculty and staff advisors regularly review student progress using tools such as MyCED, surveys, grade transcripts, clinical practice evaluations, and observation reports. The advisor uses a program checklist to track the completion of coursework and clinical practice hours. Candidates are encouraged to use this same checklist for self-monitoring and can reach out to their advisor or the program coordinator with any questions. Academic advisors in the CED Student Success and Advising Center (SSAC) are available year-round to offer guidance on academic progress and individualized support.

Candidates can track their progress using resources such as:

- Program admission requirements checklist

- Completion of program coursework checklist

- Completion of clinical practice hours checklist

- MyCED for coursework and clinical hour tracking

Candidates have access to a variety of academic resources, including:

- Student Success and Advising Center (SSAC)

- Student Support Services Program

- Learning Assistance Center

- Financial Aid

- Bob Murphy Access Center (BMAC)

Candidates may also visit the CSULB Campus Resources for a comprehensive list of academic and non-academic resources available.

The university also offers non-academic resources to support overall well-being:

- Health Resources

- Housing (Off-Campus and On Campus)

- Dream Success Center

- Pregnant and Parenting Students

- Student Health Services (SHS)

Candidates may also visit the CSULB Campus Resources for a comprehensive list of academic and non-academic resources available.

Candidates experiencing difficulties in meeting academic expectations are encouraged to seek support early. The PK-3 Program Advisor and Faculty Program Coordinator are available to help with issues related to coursework, clinical practice, CalTPA assessment, basic needs, credential recommendations, and career development.

Coursework

Candidates struggling to meet assignment deadlines and regularly attend class should immediately reach out to their instructors to schedule a meeting. Candidates should share their concerns and/or struggles and work with the instructor to develop a plan of action for them to successfully complete the course requirements. The instructor may reach out to the candidate if they have concerns regarding professionalism or academic progress. If the candidate is unable to develop an action plan with the instructor or continues to struggle to meet the course requirements, they should reach out to the program coordinator as soon as possible, or the program coordinator may reach out to the candidate.

Clinical Practice

For Clinical Practice 1 and 2, candidates who are having difficulty participating in their clinical practice visit and experiences should immediately reach out to their instructors. Candidates should share their concerns and struggles and work with the instructor to develop a plan of action for them to successfully complete their clinical practice hours. The cooperating teaching may reach out to the instructor or program coordinator if they have concerns regarding the candidate’s professionalism or classroom interactions. If the candidate is unable to develop an action plan with the instructor or the cooperating teacher, they should reach out to the program coordinator as soon as possible, or the program coordinator may reach out to the candidate.

For Clinical Practice 3 or student teaching, candidates who are experiencing challenges with their cooperating teacher should immediately reach out to their university mentor. Candidates should share their concerns and struggles and work with the university mentor to develop a plan of action for them to successfully complete their student teaching experiences. The university mentor or cooperating teacher may reach out to the program coordinator if they have concerns regarding the candidate’s professionalism or classroom interactions. If the candidate is unable to develop an action plan with the university mentor or continues to struggle to participate in their student teaching assignment, they should reach out to the program coordinator as soon as possible, or the program coordinator may reach out to the candidate. The program coordinator will work with the university mentor and cooperating teacher to develop a plan of action for the candidate to complete their student teaching experience successfully. If the candidate continues to struggle with the student teaching assignment, the program coordinator and candidate will develop a Student Success Plan (SSP), see more details below.

Professional Expectations

Candidates experiencing difficulties with professional expectations in their classes, clinical practice placements, and meetings with the program coordinator, PK-3CP advisor, College of Education staff, and university staff will meet with the program coordinator to develop a Student Success Plan (SSP). Instructors, cooperating teachers, and university mentors will evaluate the candidate’s professional behaviors and interactions, and may report the candidate to the program coordinator who will schedule a meeting with the candidate to discuss the concerns and develop a SSP or discuss alternative career pathways and options for the candidate.

When a candidate struggles with coursework, clinical practice, or professional expectations—such as late assignments, poor grades, absenteeism, or underperformance on state assessments—the PK-3 Program Advisor and Faculty Program Coordinator will initiate an intervention process. This process includes the program coordinator:

- Meeting with the candidate.

- Meeting with the candidate’s instructors, cooperating teachers, and university mentor, if applicable.

- Reviewing candidate’s instructor and cooperating teacher evaluations, if applicable.

- Reviewing candidate’s self-assessment forms.

- Observing the candidate in their classes and clinical practice sites.

- Completing the SSP form with the candidate.

Once identified, the candidate schedules a meeting with the Faculty Program Coordinator to develop an individualized Student Success Plan (SSP). The SSP is designed to provide candidates with a roadmap for success that aligns with all Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs). The SSP outlines:

- Candidate contact information

- Specific areas of concern

- A detailed action plan with steps

- A timelines to address these concerns

- Final recommendation

The Program Coordinator and/or course instructor will monitor the candidate’s progress on the SSP and document progress on identified areas of concern. Follow-up meetings and progress reviews are scheduled within 2–3 weeks. If needed, candidates may also be connected to basic needs support or referred to the CSULB CARES program for wrap-around services. At the end of the 2-3 weeks, a decision is made about the candidates next steps and all parties involved must sign the SSP.

During student teaching, the university mentor will provide weekly observations and ongoing evaluations to monitor progress. The program coordinator will meet with the university mentor to discuss the candidates progress. Follow-up meetings and progress reviews are scheduled within 2–3 weeks. If needed, candidates may also be connected to basic needs support or referred to the CSULB CARES program for wrap-around services. At the end of the 2-3 weeks, a decision is made about the candidates next steps and all parties involved must sign the SSP.

Section 7: Completion of Program

Candidates who complete all PK-3CP requirement may apply for their Initial Teaching Credential through the State of California. A credential analyst will confirm that the candidate has completed the legal requirements prior to credential recommendation. As per the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC), the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist Instruction Credential requires the applicant to have completed all of the following requirements:

- Possession of a bachelor's degree or higher from a regionally accredited institution of higher education.

- Completion of the subject matter requirement.

- Completion of a Commission approved PK-3 ECE Specialist Instruction Credential preparation program.

- Passage of Commission approved Literacy Performance Assessment and Math Performance Assessment.

- Passage of the Foundations in Literacy or a Commission approved literacy assessment aligned with the requirements of Education Code section 44320.3.

Candidates are required to establish a file in the Credential Center. A credential analyst will review all documents submitted and official transcripts within the CSULB Peoplesoft System. The candidate will receive a Credential Evaluation Information and a Preliminary Credential Evaluation, which informs them of their current program status, and that they must complete all requirements on their personal credential evaluation for credential eligibility. The candidates receive the initial credential evaluation upon application, and an updated evaluation during their final semester. When a candidate has completed their credential program and all requirements, they should contact a credential analyst through the Credential Center website.

Section 8: PK-3CP Theoretical Foundations

The conceptual framework section of the PK-3 Guide to Student Success Handbook lays out the theoretical foundation and guiding principles for effective teaching in early childhood education. Educators gain an understanding of evidence-based best practices that support young children’s learning and development within a developmentally appropriate curriculum and assessment. By integrating essential educational theories, this section provides educators with a roadmap for creating inclusive, engaging, and responsive learning environments that cater to the diverse needs of all students, regardless of their backgrounds or circumstances. The conceptual framework explores key concepts related to classroom instruction, such as constructivism, culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP), and classroom environments. We also include examples to enhance instruction.

The PK-3 credential program is designed to prepare educators to recognize that children are active constructors of their understanding of the world around them. It is their role to provide opportunities for children to initiate their own learning through exploration, discovery, and meaningful experiences that build on their prior knowledge and interests. Constructivism is a learning theory that encourages all learners to actively construct their own understanding and knowledge through hands-on learning experiences and active participation (Hong & Han, 2024). The constructivist learning approach fosters a sense of ownership and autonomy in children's learning, leading to higher levels of critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, deeper engagement, understanding of concepts, and a lifelong love of learning. This approach holds that each individual constructs their own mental or cognitive framework, interpreting their experiences within specific contexts. Key theorists such as Jean Piaget, John Dewey, and Lev Vygotsky have significantly contributed to the development of constructivist learning by emphasizing the importance of child-centered, inquiry-based approaches to education. For multilingual learners, educators can create constructivist learning environments by utilizing visuals and language supports, such as bilingual labels and picture cues, to enhance comprehension and engagement. Early childhood educators can further cultivate a constructivist learning environment by providing intentional opportunities for open-ended exploration, offering hands-on learning experiences, encouraging collaboration and communication among children, and valuing each child's unique perspectives and contributions. By fostering a supportive learning environment that appreciates children's interests and nurtures their natural curiosity, teachers can empower children to become lifelong learners.

Active Exploration

Early childhood educators have the opportunity to create meaningful ways to engage young children in active exploration and participation by providing avenues for exploration, encouraging children to make choices, and establishing intentional blocks of time for sustained engagement in exploration, interaction, and play (National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC], 2022). Active exploration encompasses hands-on learning, where children interact with materials, fostering a deeper understanding of concepts (NAEYC, 2020). By incorporating real-world experiences and interactive activities, hands-on learning facilitates children's ability to form meaningful connections and apply their knowledge practically. Examples of hands-on learning activities include sensory bins, small-world play, construction with loose parts, dramatic play based on real-life scenarios, cooking activities, and more. Through this active approach, children gain a firmer grasp of educational concepts and develop essential social skills for future success. Educators must consider their children’s interests, backgrounds, and experiences to provide developmentally appropriate hands-on practices that ignite children’s curiosity. Early childhood educators can do this by practicing the following in their classrooms:

- Create centers in the classroom that include items of interest to most children. If a group of children is fascinated by insects, consider developing a project on insects or an activity that encourages them to explore the outdoors in search of insects.

- Create activities or lessons that require small groups of children to solve problems to enhance their social skills, communication, and collaboration abilities, fostering relationships with their peers. For instance, having children work together to solve a math problem, move an object across the yard, or hang something on the classroom wall offers them opportunities to problem-solve while developing their skills collaboratively.

- For multilingual learners, integrating culturally relevant themes—such as exploring traditions from their home countries—can enhance their comprehension of concepts while building relationships with peers. For example, if a child shares a cultural activity, like a festival, teachers can design projects around it, enabling all students to engage with diversity through hands-on experiences.

- Develop real-life activities for young children based on their family experiences. If a child mentions that their favorite food is quesadillas, encourage the children to create a menu featuring their favorite foods and bring those dishes to class for everyone to sample (Wittmer & Honig, 2020).

The Zone of Proximal Development

The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is a concept that encapsulates the core principle of Vygotsky’s theory of human development (Eun, 2018). Vygotsky defined the ZPD as the gap between the level of development achieved when solving problems independently and the level that can be attained when solving problems with the assistance of more experienced peers or adults (Eun, 2018). This approach enables children to reach their full potential by scaffolding their learning experiences and fostering a deeper understanding of complex concepts. By acknowledging the ZPD, educators can provide appropriate levels of support and challenge for children, ultimately nurturing their growth and development. For multilingual learners, recognizing their ZPD means offering language scaffolding during collaborative tasks. For instance, teachers can employ modeling, sentence stems, and visual aids to assist multilingual learners in engaging with peers while enhancing their language skills.

Illustration 1.1: Zone of Proximal Development

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a teaching method in which the instructor helps learners acquire specific skills or knowledge (Zurek et al., 2014). To effectively implement pedagogical strategies in scaffolding, a teacher must understand the strengths and needs of each learner and adjust their strategy accordingly (Zurek et al., 2014). Teachers can guide children toward independence and mastery of new concepts by providing the appropriate level of support and challenge. This personalized teaching approach ensures that children are consistently challenged while receiving the necessary assistance to succeed. Scaffolding can be especially beneficial for children struggling with specific concepts or skills, as it enables them to gradually build their understanding with the teacher's support. This method encourages a growth mindset and fosters a positive learning environment where children feel supported in their academic pursuits.

Sociocultural theory focuses on children's cognitive development and higher-order thinking, highlighting the integration of social and cultural factors that influence an individual’s learning and growth through social interactions, language use, and cultural tools (Alkhudiry, 2022). Vygotsky proposed that a person’s mental abilities and understanding develop through interactions with their social environment and cultural experiences (Alkhudiry, 2022). According to Sociocultural Theory, the cultural context and social influences shape an individual’s mental abilities (Alkhudiry, 2022). The most commonly discussed concepts are the zone of proximal development and scaffolding. In early childhood settings, teachers can apply sociocultural theory in their classrooms by:

- Providing opportunities for students to work in groups, including novice and more experienced peers, allows them to share ideas and perspectives. For example, the teacher may organize the class into groups where children still developing in a particular area can be paired with students who have already mastered that skill.

- Multilingual learners can benefit from strategic pairing to support language acquisition and collaboration. For complex and challenging tasks, pairing multilingual learners with peers who speak their home language facilitates easier comprehension and support. During more relaxed, low-stress activities, pairing multilingual learners with more proficient English speakers encourages language practice and acquisition in a comfortable environment, fostering collaboration. Furthermore, creating opportunities for multilingual learners to share their cultural backgrounds —such as through storytelling or collaborative projects —promotes inclusivity and enriches the learning experience for all children.

- Guiding students' cognitive processes with techniques like asking open-ended questions and modeling behaviors or interactions.

- Integrating cultural backgrounds, items, interactions, and ways of knowing is essential. One practical approach is to communicate in a student’s home language and encourage them to use their language to share with their peers.

Young children must experience trusting and loving relationships with their teachers to nurture a healthy sense of self, develop secure attachments, and make behavioral choices that best support their development and learning (Blewitt et al., 2021; NAEYC, 2020). Relationships lay the foundation for social and emotional growth, offering children a sense of security and belonging. By establishing strong bonds with caregivers, children are more likely to feel supported and confident as they explore their environment and develop essential life skills (McNally & Slutsky, 2018). Teachers can also cultivate a nurturing environment where children feel valued, supported, and capable of overcoming challenges through conflict resolution and problem-solving (McNally & Slutsky, 2018). Moreover, when children have robust relationships with their caregivers, they are more likely to develop resilience and coping mechanisms that can help lessen the negative effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021; Lipscomb et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2021).

Engagement in the classroom refers to children's active participation, involvement, and enjoyment in learning activities (Ritoša et al., 2023). Conversely, motivation is the child’s drive or desire to achieve goals and complete learning tasks. Motivation is a key driver of engagement; when children feel motivated, they are more likely to participate actively in learning activities, explore their environment, and take on challenges. Fostering engagement is essential for intrinsically motivating children to take ownership of their learning (Ritoša et al., 2023). By promoting a sense of belonging, teachers enhance children’s overall engagement in learning, thus increasing their intrinsic motivation. For multilingual learners, fostering engagement can involve providing culturally relevant tasks and allowing for personal expression, which can enhance motivation and help all children learn about and appreciate diverse cultures (NAEYC, 2019).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy is a teaching approach that acknowledges, respects, and incorporates students’ cultural backgrounds into the learning process to enhance academic success (Gay, 2018). CRP draws upon students' cultures, languages, and experiences to make learning experiences more relevant and effective for them, going beyond basic acknowledgment of diversity. Teachers actively incorporate their students’ backgrounds and cultural experiences when planning lessons and selecting subject matter, centering student perspectives as assets in instruction (Gay, 2018). Here are a few strategies and examples of culturally responsive teaching:

- Learn about your students and their families.

- Learning the languages of the children and teaching phrases from students to build upon their linguistic skills.

- Encouraging children to speak their native language.

- Include environmental resources such as books and family photos to engage children in conversations and learning experiences about multiple elements of diversity (Durden et al., 2014).

- Incorporating materials that reflect the diverse backgrounds of students—such as bilingual books, songs, and family artifacts—can engage multilingual learners and validate their identities.

- Teach concepts and histories of the students in your class.

- Engage families in learning by inviting them to share stories, cultural recipes, or traditions to enhance home-school connections.

Research shows that the environment influences children's behavior, and a thoughtfully designed space supports their development while challenging their motor skills. Educators must create a welcoming, safe, and nurturing classroom atmosphere that helps all learners thrive (NAEYC, 2020). The classroom environment communicates to children that they are welcome and shapes their experiences and interactions; it is referred to as the "third teacher" (NAEYC, 2015). Teachers use materials and set up with intentionality to enhance instructional practices. Including culturally relevant materials—such as books, artwork, and artifacts from students' home backgrounds—fosters a sense of belonging and validates their identities. By intentionally arranging the environment to celebrate cultural diversity and encourage curiosity and engagement, teachers can create a dynamic learning space that inspires young learners to participate in their educational journey actively. A few examples of incorporating culturally relevant materials in the classroom include:

- Incorporating elements such as flexible seating, low, child-accessible shelves, and materials and pictures that reflect the children's diverse cultures and languages can create a space that encourages exploration, creativity, and independence.

- Incorporating language labels in both English and students' home languages can foster bilingualism and help children feel represented in their education environment.

- Natural light, cozy features, and engaging learning centers can further improve this inclusive environment (Pulay & Williamson, 2019).

- Teachers should use their classroom spaces to foster positive connections, collaboration, problem-solving, social skills, and a sense of belonging among students (NAEYC, 2020).

Universal Design Learning (UDL) is a framework designed to accommodate the needs and abilities of all learners by offering multiple and varied formats for instruction (NAEYC, 2020). This approach helps remove barriers to learning and ensures that all children have equitable access to educational opportunities. Differentiated instruction provides multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression, allowing teachers to make the curriculum accessible for all students and enabling them to demonstrate understanding in ways that suit their individual strengths (van Geel et al., 2022). Implementing differentiated instruction can involve providing diverse learning materials, offering choices in assignments, encouraging various forms of play, and adapting teaching methods to suit diverse learning styles (NAEYC, 2019). This includes utilizing visual aids, hands-on activities, and verbal presentations. UDL has proven especially beneficial for students with special needs and multilingual learners.

In Figure 1, the principles of UDL are summarized.

Illustration 1.2: Universal design for learning (UDL) principles (Moffat, 2022)

Section 9: Instructional Resources

Effective lesson planning is essential for fostering meaningful learning experiences in early childhood classrooms (Ramírez et al., 2017). For teachers working with children from preschool to third grade, well-structured lesson plans guide instruction, meet developmental objectives, and create purposeful learning activities (Haslip & Terry, 2023). This section of the handbook aims to equip teachers with the tools necessary to create engaging, developmentally appropriate lesson plans that support children's cognitive, linguistic, physical, motor, social, and emotional growth while fostering curiosity, creativity, and a love of learning in young children.

When planning lessons for young children, teachers employ a variety of methods to support each child’s development and interests. It is crucial to design learning experiences that reflect the unique needs of children, including their cultural and linguistic backgrounds (NAEYC, 2019). Lessons should provide opportunities for both free play and guided play. Free play allows children to explore their interests and ideas independently, while guided play involves the teacher supporting and extending children's learning through thoughtful interaction (Zeng & Ng, 2024). Both types of play are vital for creating active, collaborative learning environments where children can build important skills through exploration (Brown & Lynch, 2023).

Cycle of Inquiry

The Cycle of Inquiry (COI) is a reflective, dynamic process that early childhood educators use to observe, assess, plan, and reflect on instructional practices and their impact on children's development (Broderick & Bock Hong, 2020). The COI enables teachers to continuously refine their teaching to meet children's needs by fostering a mindset of observation, interpretation, planning, and reflection. Broderick & Bock Hong (2020) outline the COI process, which involves the following steps that teachers can enter at two different points: either starting with an Observation Record or creating a Provocation Plan to inspire further exploration inquiry.

Illustration 1.1: The Cycle of Inquiry Process (Broderick & Hong, 2020)

- Observation Record: Teachers observe and document children's behaviors, interests, and developmental progress. These records are critical for assessment and guide future actions.

- Interpreting Thinking (Divergent Thinking): Teachers analyze the observation data to understand children's thinking patterns, strengths, needs, and interests.

- Curriculum Action Plan (Divergent Planning): Based on the interpretation of data, teachers develop a plan of action that reflects children's learning goals and interests.

- Inquiry Provocation Plan (Convergent Planning): Teachers create provocations or guided experiences encouraging exploration, problem-solving, and creative expression.

- Set Up and Facilitate Play: Teachers implement the inquiry plan and facilitate play rich in learning opportunities.

- Reflective Evaluation: After facilitating play and documenting children's responses, teachers reflect on what worked, what challenges arose, and how to adjust the approach to meet learning goals better.

This cyclical process ensures that educators stay responsive to the changing needs of children and can leverage data-driven insights to enhance their practices. Through ongoing observation, reflection, planning, and evaluation, the Cycle of Inquiry ensures that early childhood educators adapt to children's needs in real time, making data-informed adjustments to curriculum, play, and teaching strategies to foster holistic development (Broderick & Bock Hong, 2020).

Lesson Planning

Districts and/or teachers often use early learning or grade-level content standards to design an entire year’s instruction, outlining key topics and skills children will explore. This comprehensive guide is frequently called a “yearly plan” or “scope and sequence.” From this, teachers can break up the annual plan into smaller units of study, chunks of learning that focus on specific themes, topics, skills, or concepts that support children’s development. These units can be further divided into daily lesson plans, which outline the specific learning activities children will engage in daily. Each daily lesson plan typically includes smaller, achievable goals that help children build upon their existing knowledge and skills. By breaking down broader objectives into daily activities, teachers can ensure that learning is accessible and engaging for all children.

By defining lesson plans in this structured way, early childhood educators create an environment where children can thrive. When designing lesson plans for young children, it’s essential to break down broader learning objectives into smaller, more manageable steps, allowing children to practice and master new skills at their own pace, which matches their developmental stage. This approach fosters a sense of achievement and confidence in meeting learning goals. Teachers have a clear roadmap of the skills or knowledge children need, helping them stay focused on the essential milestones in the learning process (Katz & Chard, 2019). Planning lesson content should involve long-term and short-term objectives, guiding teachers in creating meaningful, scaffolded learning experiences (NAEYC, 2020). Teachers can assess how well children meet each step and adjust the lesson plans as necessary, ensuring that instruction remains responsive to children's needs and developmental progress (Battal & Akman, 2022). Clearly defined lesson plans facilitate communication between teachers, parents, children, and school staff regarding what is being learned and how children are progressing (NAEYC 2019).

Developmentally Appropriate Lesson Planning Structure

Most lesson plans include essential components that enable teachers to design instructional activities tailored to the developmental needs of young learners. These plans incorporate strategies for fostering curiosity, supporting skill-building, and promoting individual and collaborative engagement. Table 2 presents a list of components commonly found in lesson plans and examples of prompts and methods that help teachers create meaningful and engaging experiences.

Components of Lesson Plans

Component | Description | |

Learning Objectives

|

| |

Standards |

| |

Introduce Concepts and Vocabulary

|

| |

Guided Practice

|

| |

Inquiry Questions

|

| |

Independent Exploration

|

| |

Reflective Summary and Assessment

|

| |

Next Steps or Follow-up Activity

|

| |

Learning Objectives

When creating lesson plans in early childhood education, teachers should thoughtfully plan each lesson to provide meaningful and engaging learning experiences for children throughout the day. Daily instructional objectives are crucial in this planning process as they outline what students are expected to learn and achieve by the end of a lesson (Katz & Chard, 2019). These objectives should be clear, specific, and developmentally appropriate, ensuring they are achievable based on each child’s individual needs and abilities (CTC, 2012). Setting clear goals for what children should learn is vital for helping teachers remain focused and purpose-driven in their instruction, which, in turn, aids in guiding children’s development and maintaining their interest in learning (NAEYC, 2019). By tailoring objectives to address each child’s unique needs, teachers can offer a more effective and engaging learning experience. While different districts, school sites, and classrooms may have their own approaches to planning, there are three key aspects to consider when creating objectives:

- Content: What skills, ideas, or academic content will children explore and learn? (This is usually based on their developmental stage or early learning standards.)

- Level of Cognition: What kind of thinking or problem-solving will children practice during the lesson? (This can include activities like exploring, sorting, or asking questions.)

- Demonstrating Understanding: What observable and measurable activities, actions, or assignments will children do to show they are learning as an indicator of success or growth? (Examples include playing, drawing, talking about what they learned in collaborative conversations, role-playing, or working together with friends.)

Here are four simple steps to help early childhood educators define lesson plans in a developmentally appropriate way:

- Set an Instructional Objective: Start by identifying a clear learning goal. For example, helping children learn to count to 20.

- Clarify the Objective: Ensure the goal is specific and meaningful. For example, define that children will learn to count to 20 by using physical objects rather than simply repeating numbers aloud.

- Break It Down Into Smaller Steps: Identify the smaller steps children need to achieve the goal. For example, first focus on counting to 5, then to 10, then 15, and finally 20. This progression allows children to build their confidence and understanding incrementally.

- Sequence the Steps Appropriately: Organize the steps in a logical order that aligns with children's developmental learning patterns. For example, begin with counting objects during playtime before moving to more structured counting activities.

The template can be utilized to organize the three parts of an objective into a statement that can be useful in preparing lessons and sharing with colleagues and students. The illustration below shows a standard 3-part objective template:

The learner will

(LEVEL OF COGNITION)

_________________________________________________________________________________

(SPECIFIC CONTENT)

by

(OBSERVABLE, RELEVANT STUDENT PROVING BEHAVIOR)

In addition to the teacher’s thoughtful planning of appropriate objectives, it is important for children to understand what they are working toward and to feel proud of their progress (Katz & Chard, 2019). Setting clear expectations and providing positive reinforcement can help motivate children to actively engage in these tasks and reach their full potential. This also fosters a sense of ownership and accomplishment, building their confidence in their abilities (Battal & Akman, 2022). A “learning goal" helps children know what they are learning and why it’s important (Bredekamp & Copple, 2022). Learning goals encourage children to participate in their own learning by making them feel successful as they progress.

Standards

Standards provide a framework outlining what children should learn by the end of the academic year (NAEYC, 2019). They offer a clear roadmap for teachers, highlighting the essential skills and knowledge for children's development and learning. By using appropriate standards in lesson planning, teachers ensure their activities support children's growth in key areas such as language, motor skills, and social-emotional development. Incorporating standards into lesson planning allows teachers to cover essential content and developmental skills that help children succeed academically. Educators should consult the California Department of Education website for the most up-to-date information standards.

Introduction to Concepts and Vocabulary

Introducing new concepts and vocabulary is a crucial first step in helping young learners establish a solid foundation for grasping lesson content (Wagner, 2021). This phase of the lesson equips students with the tools necessary to engage meaningfully with the material and express their thoughts clearly. For preschoolers through 3rd graders, the introduction of new ideas must be developmentally appropriate, engaging, and aimed at activating prior knowledge (NAEYC, 2020). Table 6 presents strategies and considerations for effectively introducing new concepts and vocabulary.

Guided Practice

Guided practice is the phase of the lesson where children receive direct support from the teacher while practicing newly introduced concepts or skills (NAEYC, 2020). During this stage, the teacher actively guides students through the learning process, providing scaffolding, feedback, and support as they work toward mastering the skill or concept. Children can begin to internalize new knowledge and skills, with the teacher offering scaffolding to ensure students are not left to struggle alone (Xi & Lantolf, 2021). The goal is to transition students from a state of dependent learning to more independent problem-solving by gradually reducing assistance.able 5 includes strategies based on the age and developmental stage of the students, ensuring that the learning experience is both developmentally appropriate and effective.

Inquiry Questions

Inquiry questions aim to foster children’s thinking. In early childhood education, cultivating a culture of inquiry is vital for promoting deep thinking and engagement (Broderick & Hong, 2020). Hollingsworth & Vandermaas-Peeler (2017) further explain that young children build knowledge and connect evidence with theory through inquiry—encompassing observation, questioning, prediction, and evaluation—especially when supported and motivated by adults. These questions are designed to provoke curiosity, encourage exploration, and invite children to express their thoughts and ideas. Inquiry questions serve multiple purposes, such as promoting critical thinking, facilitating discussions, and supporting individual understanding (Broderick & Hong, 2020). This section focuses on how to formulate and use inquiry questions effectively, aligning with constructivist learning theories that emphasize active, hands-on learning and the importance of children developing their own understanding of the world.

When creating inquiry questions for preschoolers and young learners, consider the following characteristics to ensure they are developmentally appropriate (Broderick & Hong, 2020):

- Open-Ended: Formulate questions that cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." For example, instead of asking, "Is this a circle?" Consider, "What do you notice about this shape?"

- Emergent: Develop questions that arise from children's interests and inquiries. For example, if the children are fascinated by exotic animals because they went to the zoo, you might ask, “Which animals would you like to learn more about, and why?” This approach allows for flexible and responsive teaching that builds on the topics that capture children's curiosity, fostering deeper engagement and learning.

- Relatable: Connect questions to children’s experiences, interests, and the curriculum. For example, children in California may not have many experiences in snow. Asking, “How do you think snowy weather affects what we wear?” may not connect with their personal experiences. Instead, you might ask, “What do you think we should wear on a hot and sunny day at the beach?”

- Encouraging Exploration: Frame questions that prompt children to investigate or experiment. For instance, "What happens if we mix these colors?"

- Age-Appropriate Language: Use simple, straightforward language suitable for the age group you are working with.

- Model Questioning: Demonstrate how to ask inquiry questions during group discussions or activities. Encourage children to ask questions (Hollingsworth & Vandermaas-Peeler, 2017).

- Create a Question Wall: Set up a designated space for children to post questions. This visual reminder fosters a continuous culture of inquiry.

- Encourage Peer Discussion: Allow children to discuss their questions with peers. This collaborative approach enhances understanding and builds social skills (Hollingsworth & Vandermaas-Peeler, 2017).

- Follow-up: Use children’s responses to guide future lessons and activities, ensuring their interests and curiosities shape the learning experience (NAEYC, 2019).

Independent Exploration and Practice

Independent practice refers to the opportunities provided to students to apply the skills and concepts they have learned during guided practice on their own (AISNEW, n.d.). It is a crucial part of the learning process for young children, as it allows them to demonstrate mastery, solidify their understanding, and develop self-regulation skills. Additionally, it reinforces learning, fosters independence, promotes confidence, and differentiates instruction (AISNEW, n.d.; van Geel et al., 2022; Vygotsky 1978).

How to Design Independent Practice for Young Learners:

- Set Clear Expectations: Before beginning independent practice, clearly explain the task, expectations, and criteria for success. Using visuals or simple steps can help young children understand what is expected.

- Keep It Short and Engaging: Short activities (5-10 minutes) work best for younger children for independent practice. These should be hands-on, interactive, and tied to the lesson’s learning goals. For example, in preschool, children might sort shapes or count objects; in 1st grade, they could complete a simple math worksheet or draw a picture illustrating a reading passage.

- Offer Choices and Autonomy: Giving students choices within the task— deciding which activity to do first or how to demonstrate their learning—helps foster a sense of ownership and engagement. Allowing students to explore different problem-solving methods encourages creativity and critical thinking.

- Provide Scaffolding and Support: While independent practice is meant to be done without direct teacher guidance, students, especially in the early grades, may need support. Offer prompts, visual aids, or allow students to check in with a peer or teacher if they need clarification.

- Monitor and Observe: During independent practice, observe your students to see how they are applying what they’ve learned. This will not only help you identify areas where students may need additional support but also give insight into their thinking and learning process.

- Encourage Reflection: After completing the independent activity, encourage students to reflect on their work. Ask questions like, “What did you learn today?” or “How did you solve the problem?” This helps them connect their actions to their learning and deepens their understanding.

Reflective Summary and Assessment

Assessment in early childhood education is an ongoing process that helps teachers understand and track each child's growth, learning, and development over time (NAEYC, 2019). For young children, assessment should be natural, developmentally appropriate, and integrated into daily routines and play. It focuses less on testing and more on observing and gathering information about children’s strengths, progress, and needs. Assessment is not solely about identifying gaps; it’s also about recognizing each child's capabilities and potential. By understanding where each child is developmentally, teachers can create an inclusive environment that promotes continuous learning and development while supporting further enrichment (NAEYC, 2019). Assessment tools and methods assist teachers in planning meaningful, individualized activities that support all areas of development, including cognitive, social-emotional, and physical skills.

Types of Assessments

Teachers in early childhood settings use a variety of assessment tools, including:

- Observations: Watching children engage in activities, play, or social interactions to note their behaviors, skills, and developmental progress. This is especially useful for infants and toddlers who may not communicate verbally.

- Anecdotal Records: Brief notes that capture specific moments or behaviors that highlight a child's developmental milestones or areas of challenge.

- Checklists: List specific skills or behaviors that can be checked off as children demonstrate them. For example, tracking language development or fine motor skills.

- Portfolios: Collections of children’s work (such as drawings, writing samples, or photos of completed projects) that showcase their growth over time. This method is well-suited for preschoolers and early elementary students.

- Informal Assessments: These are playful, hands-on ways to gauge a child's understanding of a concept, such as asking a kindergartener to count blocks during free play or encouraging a preschooler to retell a favorite story.

Next Steps or Follow-up Activities

Teachers utilize the assessment results to plan upcoming lessons. Children who did not meet the objectives or struggled to grasp the new concepts may need additional support and targeted activities to achieve those objectives. The teacher might observe that some children are meeting the objectives; consequently, they will plan the next lesson to enhance and enrich their learning experiences and advance them to the next level.

Classroom expectations and rules are crucial to teaching in early childhood education, just like any other subject. These elements should be flexible and tailored to fit the children’s developmental levels and the teacher’s style, fostering a positive learning environment where children feel safe, secure, respected, and supported in making appropriate decisions about their behavior (Battal & Akman, 2022). Establishing expectations and maintaining boundaries isn’t about controlling behavior—it's about teaching and reinforcing the behaviors and skills children need to thrive socially and emotionally (August 2021). Clear classroom expectations and rules establish a predictable environment where children learn to make choices, solve problems, and take responsibility for their actions (Battal & Akman, 2022). By creating a safe and predictable environment with clear expectations and rules, children can concentrate on learning and developing essential life skills such as cooperation, problem-solving, and self-regulation.

Category | Strategy | Description | Visual/Symbol Example | |

Preschoolers/TK | K-3rd grade | |||

Engaging Activities | Exit Slip / Evidence Bag | Students reflect on the lesson and share what made learning easy, difficult, or what they still need to know. | Use pictures or drawings instead of written text to reflect understanding. | Use sticky notes, whiteboards, scraps of paper, journals, etc. with a writing instrument. |

Fishbowl | A formal discussion with two circles: inner circle (discusses) and outer circle (listens, evaluates). | Adapt to a group discussion where children use "talking sticks" or toys to signal when it’s their turn to share. | Two concentric circles | |

Four Corners | Students move to different corners of the room to discuss a prompt based on their corner's theme. | Use simple themes (colors, shapes, animal sounds) to guide students to each corner. Focus on movement and play. | Four directional arrows pointing to corners | |

Spectrum | Students line up based on their opinion (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree). | Simplify to a “Yes/No” or “This side/That side” for physical movement. Incorporate visuals (pictures or objects). | A line with “Agree” and “Disagree” | |

Collaborative Learning | Think-Pair- Share | Think independently, pair up to discuss, and share with the group. | Use “Think-Pair-Say,” where students take a moment to think, share with a partner, then share with the group. | Thought bubble → Two people → Group sharing |

Jigsaw | Students become experts on different sections of text and share their knowledge with others. | Use small group activities where each group works on a part of a simple story or activity (e.g., sorting shapes, colors, or animals). | Puzzle pieces fitting together | |

Numbered Heads | Students number off in teams, discuss answers, and when a number is called, the corresponding student shares. | Numbering can be done through songs, colors, or toys. Keep the groups small and incorporate movement. | Four numbered circles | |

Organizing and Reflecting on Learning | Graphic Organizers | Tools like Venn Diagrams, concept maps, or Thinking Maps to visualize knowledge and concepts. | Use simple graphic organizers like sorting trays, pictures, or cutouts to organize objects by category (e.g., animals, food, colors). | Venn diagram |

K-W-W-L | What I Know, Where I Learned It, What I Want to Know, What I Learned. | Adapt to visual symbols. Focus on “What I know” and “What I want to know,” and use drawings to reflect understanding. | Flowchart or grid with four sections | |

Quick-write / Reflection | Students write for a set amount of time about a specific topic to reflect on their learning. | Substitute with drawing or dictating responses. Incorporate interactive reflection (e.g., using felt boards or manipulatives). | Pencil with lines showing text | |

Resources

- CA Preschool/Transitional Kindergarten Learning Foundations

- Common Core State Standards

- Development and Research in Early Math Education (DREME)

- National Association for the Education of Young Children

Teacher Lunch

Students choose a month and day in the classroom calendar to schedule a one-on-one lunch with the teacher.

- Students engage in conversation with the teacher during lunchtime.

Exit Slip/ Evidence Bag

1 – What made learning easy for you today?

2 – What made learning difficult for you today?

3 – What do you still need to know before we move on?

4 – What did you learn today?

5 – What should our next steps be?

Students can answer self-selected question/s or teacher-selected question/s using sticky notes, whiteboards, scraps of paper, journals, etc.

Fishbowl

This strategy provides students an opportunity to engage in formal discussion and to experience roles both as participants and as active listeners; students also have the responsibility of supporting their opinions and responses using specific textual evidence.

- Students are asked to engage in a group discussion about a specific topic – there will be two circles: Inner circle students will model appropriate discussion techniques… while the outer circle students will listen, respond, and evaluate.

Four Corners

The teacher posts questions, quotations, photos, etc. in each of the corners of the room. The teacher assigns each student to a corner… or students choose.

- Once in the corner, the students discuss the focus of the lesson in relation to the question, quote, etc…

- At this time, students may take notes, report out, or move to another corner and repeat the process…

- After students have moved or completed the activity, they should be encouraged to reflect on changes in their understanding of the content

Idea Wave

- Each student lists 3 to 5 ideas about the assigned topic.

- A volunteer begins the “idea wave” by sharing one idea

- The student to the right of the volunteer shares one idea; the next student to the right shares one idea.

- The teacher directs the flow of the “idea wave” until several different ideas have been shared.

- At the end of the formal “idea wave,” a few volunteers who were not included can contribute an idea.

Jigsaw

- Students read different passages from the same text (or selections from several texts) becoming the expert with the specified text.

- The “experts” lead discussion or share the information from their specific reading with a specific group or the entire class.

K – W – W – L

What I Know – Where I learned it – What I want to Know - What I Learned

This strategy helps students organize, access, and reflect on learning which increases comprehension and engagement.

- To activate prior knowledge ask, “What do I know?”

- To acknowledge the source and ask, “Where did I find the information?

- To set a purpose, ask, “What do I want to know?”

- To reflect on a new learning, ask, “What did I learn?”

Graphic Organizers

A graphic organizer is a communication tool that uses visual symbols to express knowledge, concepts, thoughts, or ideas, and the relationships between them. The main purpose of a graphic organizer is to provide a visual aid to facilitate learning and instruction. Many districts use Thinking Maps© but other common graphic organizers include Venn Diagrams and concept maps.

Numbered Heads

Students number off in teams, one through four.

Teacher asked a series of questions, one at a time.

Students discuss possible answers to each question, for a set amount of time (30-90 seconds). Teacher calls a number (1-4), and all students with that number raise their hand, ready to respond.

Post-It Voting

Students use sticky notes with their initials to vote or comment and put up in designated areas of white board or voting chart.

Can be used:

- to give rubric scores for an anchor paper

- Multiple Choice answers

- Categorizing information/input

- Collect class data for upcoming unit of study (pre-test option)

Quick-write / Reflection

Use a quick-write to activate background knowledge, clarify issues, facilitate making connections, and allow for reflection.

Students write for a short, specific amount of time about a designated topic related to…

Socratic Seminar

Use a Socratic Seminar to help students facilitate their own discussion and arrive at a new understanding in which they learn to formulate questions and address issues in lieu of just stating their opinions. Students engage in a focused

discussion in which they ask questions of each other on a selected topic; questions initiate the conversation which continues with a series of responses and further questions.

Spectrum

Use a spectrum when asking for student opinions on a topic or question.

Place a line on the chalkboard or masking tape on the floor in front of the room.

Label one end of the line “Strongly Agree” and the other end “Strongly Disagree.”

Students line up according to their opinion on the topic, most important/least important, greatest effect/least effect, expert/knowledge line (level of student expertise.)

Think - Pair - Share

THINK: Take a minute to first silently and independently think about your own answer to the question(s).

PAIR: turn and face your partner so you can discuss your answers face to face. Listen carefully to your partner’s answers, and pay attention to similarities and differences in your answers. Ask for clarifications.

SHARE: Be prepared to share your opinions with the class.

What’s the Same/Different?

This strategy involves simply asking students to compare two or more items and describe how they are the same or different. Excellent as an anticipatory set to activate prior knowledge or build background knowledge.

Multiple Intelligences

Multiple Intelligences theory (MIT) was developed by Howard Gardner to highlight the diverse ways in which individuals learn and process information (Gardner, 1987). MIT has evolved since its inception and includes nine intelligences:

- Linguistic: The ability to use language, the sensitivity to word and phrase order, and verbal meaning.

- Logical-mathematical: The ability to use patterns and solve problems.

- Spatial: The ability to learn through the visual world, the sensitivity to images, and visual memory.

- Bodily-kinesthetic: The ability to coordinate and operate technological tools.

- Musical: The ability to recognize, create, and enjoy music.

- Interpersonal: The ability to understand and sympathize with people, create social relationships, and solve conflict.

- Intrapersonal: The high personal awareness and personal motivation.

- Existential: The ability to tackle deep questions about life and human existence

- Naturalistic: The ability to understand nature and characterize plants and animals.

Gardner (1987) says that every person possesses a unique combination of these intelligences by recognizing and valuing these differences, teachers can create a more inclusive learning environment that caters to the diverse needs and strengths of all students. Teachers can use the Personalized Learning and MI Theory lesson template to create assignments based on a student's personalized learning.

Personalized Learning and MI Theory

Personalized Learning

MI Integration | My Community (1st Grade Social Studies) | Math | Literacy |

Linguistic Verbal | Make a book about your favorite things in your community. | Create a skit, or poem that uses math vocabulary. | Write a book about what you did over the weekend with your family. |

Logical Math | Choose things to count in your Community (e.g., houses on your block, street lamps) | In groups | Read a book that includes math. |

Visual-Spatial | Take photos of your city and put them together in a photography exhibit. | Play a game where children can use 3D manipulatives (blocks, cubes, legos) | Play a sight word scavenger hunt |

Bodily-kinesthetic | Go on field trips to different areas of your community and create "social stories" of the trips.

| Go to the outside playground and count the different plants, trees, bushes, and flowers you may see. Write them down and organize them in different sections, then add how many you found in total and separately in their group. | In groups, write a play and present your play to your peers. |

Musical | Make an audio recording of the sounds heard around your community. | Listen to songs about different math concepts. Then, create a song of a math concept. | Create a song that is based on a book you have read. |

Interpersonal | Contact a local historian who can visit the school and talk about the history of your community; interview members of the community about the history of your town. | Get together with a small group of peers to play a math game. | Write and create a book of your favorite person in your life. |