The Authenticity Project

Exploring the Role of Authenticity in Informal STEM Learning

Museums, science centers, zoos and other informal science education institutions often focus on providing authentic objects as central to a particular learning experience, from the Field Museum's T-Rex Sue to the California Science Center's Endeavor Space Shuttle. Such attractions, in the form of objects (large and small), settings and activities, are seen as a way to engage, inspire or inform the public. It seems that 'The Real Thing' has been seen by educators, exhibit designers and program developers as a driver for public engagement in these places—yet there is some questions as to this long-standing perspective relates to learning.

For this NSF-funded project (AISL, #1906889), we sought to develop a better understanding of the role of authenticity in informal science learning by first looking at what researchers and other experts in education and adjacent disciplines like tourism, marketing, and cultural studies, have learned about the role of authenticity and its influences on interest, attitude, and even learning. We hoped that this exploration of scholarly literature might help us better understand the role of authenticity in learning.

The first phase of our project involved examining existing literature reviews (syntheses of different research efforts and topics) as well as books and other existing publications that might provide us with underlying ideas and agreed-upon assumptions. Yet as we started this dive, one thing became clear very quickly—our assumption that authenticity can be viewed as a clear-cut feature or characteristics was wrong. Our first step then became clarifying just what makes something authentic.

What is Authenticity?

Across the literature, we found a variety of different perspectives on authenticity or what makes something authentic. Some referred to refer to authentic as a characteristic of something that possesses originality in design, being the first of its kind, and not a copy or imitation. Yet, others suggest that authenticity is not a binary concept (is it authentic or not?) but rather a continuum. Also, throughout the literature, there is discussion of the subjectivity of authenticity--that is, the idea that authenticity is a social construct or at the very least, a perception determined by the individual.

As we continued our exploration of the research and attempted to examine how authenticity (of an object, a setting, an activity) might affect learning, or any outcome for that matter, it became clear that the individual played a critical role. It would seem that the perception of authenticity, as defined by the individual and shaped by experience, expectation, or environment, is what counts. With all that in mind, we might define authenticity as:

A quality assigned (to an object, setting, activity, etc.) when a person makes a judgment that something is the 'real thing'

Or

A quality assigned when a person makes a judgment that something feels 'true to life,' conforming with one's prior conceptions about a person, place, experience, or thing

Across the literature, we found a variety of different perspectives on authenticity or what makes something authentic. For instance, Gilmore and Pine (2007) refer to authenticity as that which possesses originality in design, being the first of its kind, and not a copy or imitation. Evans, Mull, and Poling (2002) similar describe authenticity, from a child's perspective in terms of what it is (‘real’, first of its kind, awe-inspiring) as well as what it isn't (not a fake, not an illusion, not simulated.)

However, other researchers and authors suggest that authenticity is not a binary concept (authentic or not) but rather a continuum. Geurds (2013) suggests that "Objects and their interpretation are so pliable as to eventually overcome being branded 'inauthentic' by achieving a 'sufficient' degree of authenticity…instead creating degrees of authenticity."

Similarly, Lovell and Bull (2018) posit that "Authenticity isn't 'black and white;' rather there are gradations that separate authentic from fake." In each of these cases, the underlying assumption is that the authenticity (and perhaps subsequent value of authenticity) is dependent on the individual--their background, beliefs, experiences and motivations.

Throughout the literature, there is discussion of the subjectivity of authenticity--that is, the idea that authenticity is a social construct (Smith, 1999) or at the very least, a perception determined by the individual. Gilmore and Pine (2007) suggest that "the sole determinant of the authenticity… is the individual perception of the offering. Because our experiences with offerings happen inside of us, we become the sole arbiter of what is authentic for us."

The concepts of 'cool authenticity,' referring to the 'genuine-ness' of an object, environment, experience as determined by an external expert and based on scientific/historical knowledge, and 'warm authenticity,' involving personal or subjective feelings related to an individual's or community’s beliefs about the authenticity of a practice or experience in which they engage, reflect drastically different approaches to this concept (Khanom et al., 2019).

For some, authenticity is examined in terms of power. Who determines what is "authentic" identity, cultural production, or traditional practice? Who has the "authority to authenticate?" (Bruner, 1994). This includes looking at how people construct and define authenticity to serve specific purposes, and how these constructions of authenticity can be linked to identity (for example, who or who is not considered an authentic authority of cultural knowledge or practices).

Along this line, numerous authors appear to argue that a sense of authenticity can be curated or enhanced by surrounding objects with robust context: "The story makes an object 'real' or authentic--even if the object is not entirely real (e.g., reconstruction of a whale.) However, without context or history of scientific information, the object lacks cachet and may not be seen as 'authentic' or important" (Payne 2019, p184).

Authenticity in Informal Science Environments

For purposes of this project, we were interested specifically in the qualities of authenticity as they relate to objects, settings or activities—key elements often part of informal learning environments. By object, we refer to a physical or virtual (digital) 'thing': a fossil, a telephone, an animal, a virtual representation/hologram, etc. Settings refer to physical or virtual spaces/places at which something occurs, is designated to occur, or has occurred. Settings can be designed (simulated rainforest in a zoo, a dinosaur exhibit or a virtual space station online) or 'natural' (an actual rainforest, an archaeological excavation). Finally, we consider activity to be task or series of tasks in which someone participates. The activity might involve particular objects (e.g. using a microscope, excavating a replicated fossil) or occur in a particular setting (e.g., speaking with an actor in a historical home, gathering water samples in a local stream).

What We Did

Given how the question (or assertion) of the importance of 'authentic' popped up again and again in discussion of practice in informal science education, we wanted to see just what was known about authenticity and learning. We also recognized that because the study of informal learning is distributed across many disciplines, we would need to look beyond what has been studied in education and museum studies. We conducted a systematic review of published literature, examining both theoretical perspectives, presented in books and reports and literature reviews, as well as peer-reviewed published research and evaluation work that examined authenticity and its effect on learning (and other outcomes).

This systematic review of literature involved two phases. Phase I focused on prior literature reviews and syntheses, as well as 'gray' literature that included published reports, books and chapters, and related information sources (both peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed). The initial Phase I search yielded overarching ideas related to the topic of authenticity and how it is conceptualized across different disciplines and different contexts. These claims and perspectives began to shape (and reshape) our ideas of authenticity as well as clarify how the concept is addressed in different disciplines such as tourism and consumer studies. Critical articles and book chapters identified from this first phase of review (i.e., those that generated relevant claims) were examined to generate a list of common keywords that could be used for a targeted search of empirical (research-focused) literature. After some adjustments, the search parameters for Phase II were identified.

Phase II, our deep dive into the empirical literature, started with sixteen separate searches using the Web of Science database and the key words identified from Phase 1. Further refinement of the almost 1000 articles discovered involved a review of titles and abstracts (and sometimes a deeper look at research findings) using a rubric to determine whether the paper examined one of three contexts of authenticity (object, setting, activity), whether it presented research (as opposed to a review or synthesis, or position paper, for instance) and whether it examined outcomes of some kind. Articles failing to meet all three of these criteria were removed. Additional examination of outcomes at this level involved coding as a learning outcome (as aligned with the NRC six-strand model of science learning) or more general outcomes (satisfaction, return visit, behavior change, etc.). Coding efforts were discussed among 2 reviewers to improve reliability. A final count of 167 research-based articles identified for in-depth analysis.

To facilitate analysis of the research articles, a summary form was developed to identify key findings and claims as well as capture details related to research design (qualitative vs. quantitative), context, project goals, and types of outcomes examined (learning vs. affect/satisfaction). An extensive review of these summary forms by the research team led to the development of key findings and a preliminary model explaining the role of authenticity in an informal science learning setting.

What We Found (or Didn't Find)

Our efforts to understand what was already known about authenticity revealed that there were generally more assumptions as to how authenticity impacts learning than research to to back it up.

Few Published Studies

There are only a handful of published research studies that examine authenticity in museum or informal learning settings. While a few of these look specifically at learning outcomes (Carsten Conner & Perin, 2020; Eberbach & Crowley, 2005), others are focused on visitors' perceptions of authenticity and how it changes their interest or attitudes toward an object. (Schwan & Dutz, 2020; van Gerven et al., 2018).

Degrees of Authenticity

There is a more prominent discussion of authenticity in the field of tourism. These researchers examine how authenticity, or lack of authenticity, affects outcomes such as satisfaction, interest, and likelihood of return visit, among others. Perhaps unsurprisingly, none of these studies attempted to link authenticity and learning or knowledge-building. Nevertheless, this work points to the idea that authenticity may affect engagement with an object, setting or activity. Such findings have implications for informal learning where engagement and interest can be seen as starting points for deeper learning experiences.

In our work, we found that authors established and referenced a variety of definitions for what they consider to be authentic or real. For instance, Gilmore and Pine (2007) refer to authenticity as that which possesses originality in design, being the first of its kind, and not a copy or imitation. Evans, Mull, and Poling (2002) similarly describe authenticity, from a child's perspective, in terms of what it is ('real,' first of its kind, awe-inspiring) as well as what it isn't (not a fake, not an illusion, not simulated.) Yet other authors, especially those within the fields of anthropology, tourism, and consumer behavior, suggest that authenticity is not a binary concept (authentic or not) but rather a continuum. Geurds (2013) suggests that "Objects and their interpretation are so pliable as to eventually overcome being branded 'inauthentic' by achieving a 'sufficient' degree of authenticity, thereby breaking the binary debate of authentic versus inauthentic, instead creating degrees of authenticity." Similarly, Lovell and Bull (2018) posit that "Authenticity isn’t 'black and white;' rather there are gradations that separate authentic from fake."

Perceived Authenticity

As we continued to make sense of these studies, we began to see that it wasn't necessarily the authenticity of the object, setting or activity that affected learning, but rather the perception of authenticity by the learner (or visitor) that had the potential for impacting their experiences. By examining perceived authenticity, we are able to take into account the different, sometimes nuanced, ideas around the importance or relevance of authenticity held by learners. This approach may provide a more accurate interpretation of the effects of interactions with 'the authentic' on learning and behavior while avoiding a more authority-laden or unquestionable conceptualization that could ultimately discount the learner's voice and prior experience.

Making Sense of It All

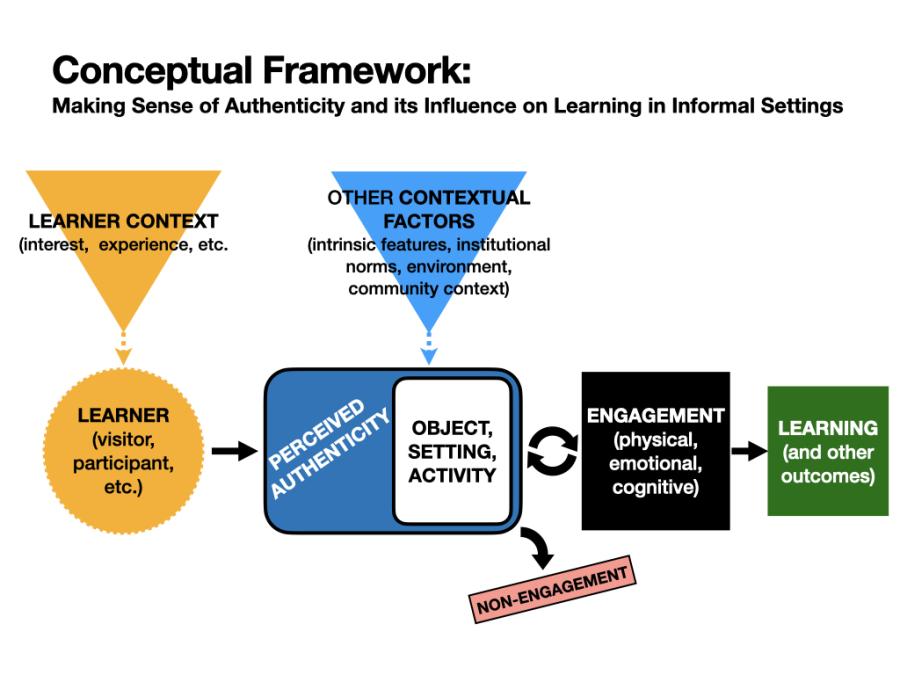

Our synthesis of the literature related to the idea of authenticity led to the development of a preliminary model that would not only help explain factors that can influence a learner's or visitors perception of authenticity, but also explain how these perceptions might influence engagement, and subsequently, learning. This 'authenticity lens' attempts to center the learner (visitor, participant) amidst different influences or factors that subsequently shape their perceived authenticity, which in turn guides their engagement with the object/setting/activity centered in their informal learning experience.

Whether a learner perceives something to be authentic in a particular situation is influenced by a variety of personal variables, including prior knowledge and experience, expectations related to the experience (Hede et al., 2014; Walter, 2016), as well as their personal definition of authenticity, and subsequent value for this characteristic. Furthermore, the importance of authenticity, more generally, may vary with different situations and experiences.

Our research also suggests that the experience of authenticity can also be shaped by several contextual factors related to the object/setting/activity itself. For instance, the intrinsic characteristics of the object or setting (its relative size and scale, whether virtual or real, quality of replication) can influence perceived authenticity. Related to this is the physical space where the experience takes place. How an object is presented—where or how it is situated within an exhibition space (is it touchable or behind glass)—can impact perceptions of authenticity. Institutional context, including desired (learning) outcomes for a particular exhibit or experience, as well as institutional mission and even organizational norms or traditions may also influence how an individual perceives an object, setting or activity within their museum experience. Finally, it is important to consider the community context within which both the institution (and the learner) are situated. While an object or activity may be presented in a way that contributes to the perceived authenticity of one visitor, another visitor, for which the object or activity holds a different cultural significance, may perceive these as inauthentic by virtue of how they are displayed or how their importance is communicated. This may be especially true in situations where exhibits are linked to imperialist practices of the past.

A learner's initial perception of authenticity will influence how they engage (or don't engage) further with an object, setting, or activity. Engagement, in this case, is defined very broadly as a physical, cognitive or emotional interaction or connection. Furthermore, the act of engagement may itself influence the learner's perceived authenticity through their negotiation of the different factors (prior knowledge, physical space, institutional context, etc.) that may have initially affected their ideas about the value or relevance of the object or activity. In other cases, however, the initial assessment of authenticity (or rather inauthenticity) may simply turn the learner away from any meaningful engagement, blocking the opportunity of the object, setting or activity to mediate any meaningful learning.

As mentioned, there are limited studies that examine whether perceived authenticity of an object, setting or activity specifically or explicitly impact learning. However, there is a larger body of literature that considers how perceived authenticity impacts broader outcomes such as return visits (Loureiro & Blanco 2021; Fu 2019), satisfaction (Girish 2017; Hernandez Mogollon 2013), engagement and positive recommendations (Curran 2018; Kaur & Kaur 2020). We would suggest that such outcomes, especially those involving positive affect and extended engagement, might be considered precursors to learning in informal settings.

The National Research Council report Learning Science in Informal Environments (2008) suggests that science learning might be better conceived as a series of strands and outcomes, including experiencing interest, excitement and motivation. This framework for thinking about science learning in informal environments 'places special emphasis on providing entrée to, and sustained engagement with, science—reflecting the purview of informal learning—while keeping an eye on its potential to support a broad range of science-specific learning outcomes' (p 24). Using this framework, we might consider positive experiences, extended engagement and satisfaction, as described in our model, as providing fertile ground for entry into science learning.

Key Discoveries

Consumers (learners, tourists, visitors) generally value authenticity.

A large sample (n=703) of visitors to science & technology centers, natural history museums, and cultural history museums agreed that authentic objects give weight and depth to an exhibition theme (Schwan & Dutz, 2020). They are lasting, tell stories, give visitors a sense of how it truly was, help them understand, and make them curious. That said, replicas contextualized within the exhibits did not detract from the visitors' experiences. So, in this study, it is not necessarily an object's 'realness' that matters but its perceived authenticity.

Children (ages 8-12) ranked authentic fossils higher than replicas when asked what objects belong in a museum (van Gerven et al., 2018). The reasons children gave for valuing the real fossils included their appearance, ideation (real is better), association (real fossils remind them of real dinosaurs), and contagion (a real fossil has the past 'attached' to it).

Authenticity can be linked to positive outcomes.

These include satisfaction, motivation to return or share with others, increased engagement, and identity development.

An ethnographic study by Cliffe et al. (2021) describes how audio augmentation of a 1950's television and vintage radio expanded the piqued visitor interest and attention, improved understanding of the objects' cultural significance, helped users connect to personal memories, and encouraged a desire to know more.

As part of a museum-based science education program, diverse high school students from New York City demonstrated greater competence in several science skills after spending a summer working alongside museum scientists (Habig & Gupta, 2021). Participants also believed that they were more competent in those skills and maintained an interest in scientific research over time and used their new skills with greater frequency outside the program. Researchers described the museum-based program as an authentic activity.

According to people who visit museums frequently in the United Kingdom (n=308), one factor that makes a museum cool is its authenticity, its use of energetic exhibits that stay true to the museum's "roots and essence." Visits to 'cool' museums can generate feelings of self-worth and achievement, or authentic pride, and authentic pride can inspire a passionate desire to revisit the museum (Loureiro & Blanco, 2021).

'Authentic' may not be better.

Although authentic objects/settings/experiences may afford certain outcomes that replicas/simulation cannot, the reverse may be true as well.

For museum visitors examining ancient artifacts, having the real object in front of them was notUnable to load the graphicas helpful or engaging as having the real object combined with 3D replicas and 3D digital reconstructions. Visitors could touch 3D replicas to understand how they might be held and used. Using VR, they could rotate objects, use color changes to interpret texture, and zoom in on features that sparked their curiosity. While visitors made size misjudgments when exploring objects in VR, their engagement was higher, leading to more self-guided exploration. (Di Franco, P., Camporesi. C., Galeazzi, F., & Kallmann, M., 2015)

Virtual reality snorkeling at the Great Barrier Reef inspires the same emotional connections as actually snorkeling at the Great Barrier Reef, with or without interpretation. Emotional connection to the natural environment inspired limited intentions to adopt conservation behaviors – in the virtual reality group, not the group that visited the reef. (Hofman, K., Walters, G., & Hughes, K., 2022)

Families engaged in more conceptual talk at a replicated permafrost tunnel at a science museum in Oregon compared to families at the real research-based permafrost tunnel located in Alaska. The content of the conceptual talk was very similar at the two locations, connecting back to information in the tours provided at each site. In contrast, the real tunnel, however, afforded more perceptual talk—discussions built from sensory experiences such as odors and temperature. This rare comparison study suggests different contexts (authentic vs. replicated) can afford learning in different ways. (Carsten Conner, L. D. & Perin, S. M., 2020)

Visitors may negotiate with the inauthentic to construct their perception of authentic.

This process may occur when it enhances their experience, supports expectations, or promotes desired outcomes.

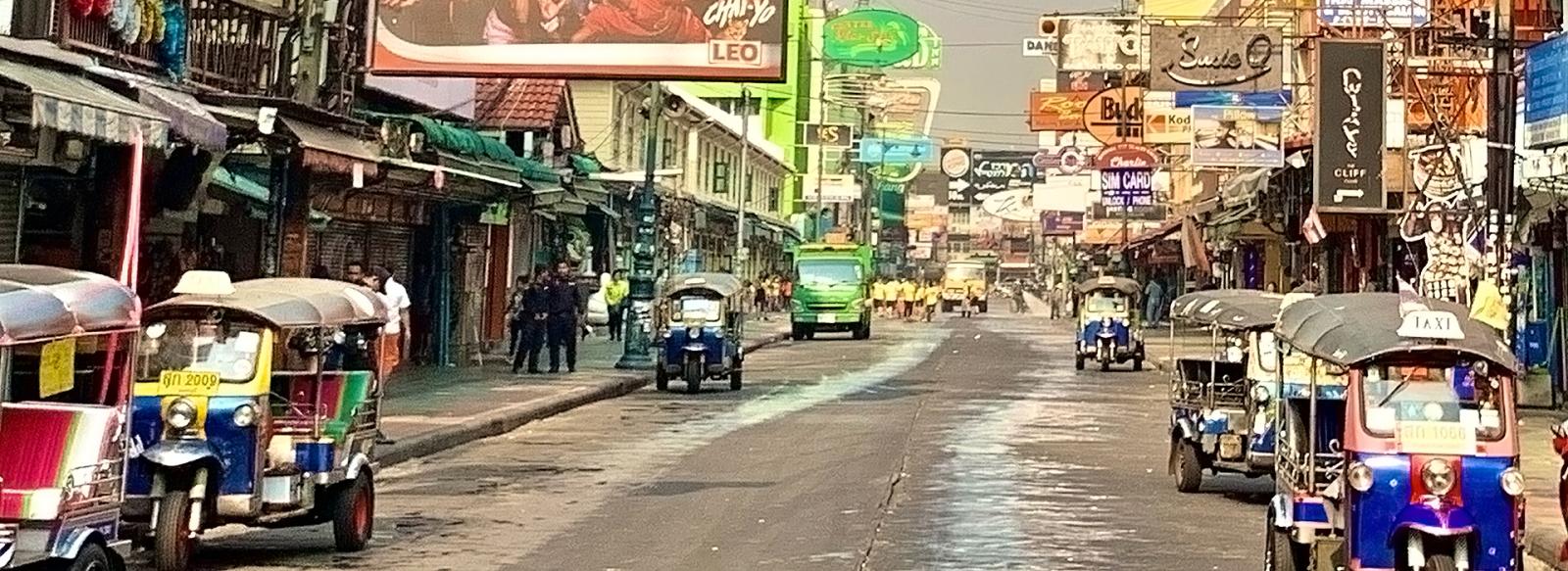

Many visitors to a staged hill town in Thailand expected objective authenticity only to be disappointed by the commercial feel of the site, high prices for souvenirs, and the modern behaviors of the hosts. Other visitors, however, negotiated with the idea of authenticity by accepting inauthentic elements of the staged site as true to how its residents balanced modern life with efforts to preserve historic hill town culture. (Walter, P. G., 2016)

Negotiating with the inauthentic may begin with curators and institutions. Kungfu masters who keep the traditions of Hakka Kungfu alive through public demonstrations are increasingly rare, so curators of a Hakka Kungfu exhibit had to reconsider what constitutes an authentic Kungfu experience. To capture the fading art form in a lasting and transportable exhibit, designers situated virtual reality experiences and holographic displays among old photos, short documentary films, and real weapons. Researchers found that visitors preferred the virtual and digital technologies and that the blend of real with not real afforded "active engagement with an intangible culture." (Lo, P., Chan, H., Tang, A., Chiu, D., Cho, A., See-To, E., Ho, K., He, M., Kenderdine, S., & Shaw, J., 2019)

Where Do We Go From Here

More Studies are Needed

Based on project findings, as well as feedback from practitioners, there are several areas of interest that could be fruitful opportunities for future research, including:

Explicit examination of learning outcomes. While we found a solid body of literature around how authenticity might be conceptualized and while we found some evidence how authenticity might influence enjoyment, participation, or recommendation to others, we found little direct evidence on how the degree or presence of 'authenticity' impacts learning outcomes.

Comparison studies. A traditional experiment allows for comparison of outcomes under different treatments, such as examining the different learning outcomes when using a real fossil vs. a 3D virtual replica. Only a handful of studies throughout the literature have attempted such comparisons between authentic and inauthentic objects/settings/activities. Such work would further strengthen our understanding of whether having the real thing influences or enhances learning.

Authenticity and Living Collections. Discussions that arose during the Los Angeles practitioner workshop pointed to questions related to trade-offs between making the spaces more authentic or "nature-like" versus making it easier for visitors to see the organisms, unencumbered by context.

Testing the model. The proposed model suggests multiple factors that can influence learners' perceptions of authenticity as well as their engagement. Research to better understand these influences, via both quantitative and qualitative means, would help confirm or reshape our ideas regarding this authenticity-lens on learning.

Implications for Practice

How might key ideas from this synthesis inform decision-making for educators, designers, and curators in the field of Informal (Science) Education? For example, how might a designer incorporate some of these ideas into their decision-making when designing an exhibition around space travel. Are artifacts that have made their way to space (and back) needed to convey the key messages? Are visitors more likely to visit the proposed exhibit, which allows them to engage with content or science messaging, if objects were genuinely used by astronauts?

The shift from research (or research synthesis) to practice is not trivial. Not only does it require thoughtful application of new ideas to current procedures and ways of thinking, but it must also overcome years or decades of assumptions and traditions that are pervasive in these institutions. The synthesis described in this report reveals that there are limited empirical data around how the characteristic of authenticity might impact learning outcomes—this may suggest that few are willing to question (or have time to question) assumptions around authenticity and its role related to learning in informal settings.

In some ways, this project has introduced more questions than answers related to the role of authenticity in informal science learning environments. A dissemination meeting with educators and other museum professionals in February 2023 resulted in a range of practice-related questions, including:

- Does the inauthentic nature of live animal exhibits hinder learning?

- Is there a way in which virtual reality experiences can supplement objects that cannot be touched or held without being too distracting?

- How can I ensure that students have authentic experiences?

Embedded in each of these questions are different definitions of 'authentic,' influenced by experience, institutional traditions, and even new ideas from the workshop. And each of these questions, if answered adequately, has the potential to support new practices.

Clearly, more work is needed to apply the key ideas from this project to improve practice. However, it would seem that there are two essential messages for practitioners in informal settings that emerge from this synthesis. First, if authenticity is subjective and based on the perception of the individual, then it is important to revisit assumptions regarding how authentic objects or settings actually support learning. This may very well involve some data-gathering to look at how authenticity impacts the visitor experience—specifically as it relates to learning. At the very least, it might entail conversations with visitors and other stakeholders to better understand their perspectives. Second, it would seem that the importance of authenticity may depend on the kind of learning outcomes desired for a given exhibition or program. For instance, if the goal is to help visitors understand how an animal skull of an ice-age animal provides clues to what they might have done to survive, it may not be necessary to have the original fossilized skull—a replica may be fine for developing such understanding. Hopefully, additional research and evaluation related to the role of authentic objects, settings, and activities, coupled with a willingness to balance visitor interests ('I want to see the original') with institutional goals ('Visitors should learn,' 'Visitors should feel connected to the museum,' 'Visitors should return') will further our understanding and practice related to 'the real thing.'

Learn More

These articles and chapters were particularly helpful in their conceptualization of Authenticity or their research efforts related to understanding the impacts of Authentic objects, settings, or activities.

- Bunce, L. (2019). Still life? Children's understanding of the reality status of museum taxidermy. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 177, 197-210.

- Carsten Conner, L. D., & Perin, S. M. (2020). Learning from the real versus the replicated: a comparative study. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 10(3), 266-276.

- Di Franco, P. D. G., Camporesi, C., Galeazzi, F., & Kallmann, M. (2015). 3D printing and immersive visualization for improved perception of ancient artifacts. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 24(3), 243-264.

- Eberbach, C., & Crowley, K. (2005). From living to virtual: Learning from museum objects. Curator: The museum journal, 48(3), 317-338.

- Gilmore, J. H., & Pine, B. J. (2007). Authenticity: What consumers really want. Harvard Business Press.

- Girish, V. G., & Chen, C. F. (2017). Authenticity, experience, and loyalty in the festival context: evidence from the San Fermin festival, Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(15), 1551-1556.

- Hede, A. M., Garma, R., Josiassen, A., & Thyne, M. (2014). Perceived authenticity of the visitor experience in museums: Conceptualization and initial empirical findings. European Journal of Marketing, 48(7/8), 1395-1412.

- Lovell, J., & Bull, C. (2017). Authentic and Inauthentic Places in Tourism: From Heritage Sites to Theme Parks.

- Pyne, L. (2019). Genuine Fakes: How Phony Things Teach Us About Real Stuff.

- van Gerven, D., Land-Zandstra, A., & Damsma, W. (2018). Authenticity matters: Children look beyond appearances in their appreciation of museum objects. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8(4), 325-339

- Walter, P. G. (2016). Travelers' experiences of authenticity in "hill tribe" tourism in Northern Thailand. Tourist Studies, 16(2), 213-230.

- Authenticity in Practice: Examining the Perspectives of Informal Educators. Poster presentation at the Visitor Studies Association (VSA) Annual Meeting (July 2022). (updated on 12/30). VSA Poster (PDF)

- Does the Real Thing Matter? Making Sense of Authenticity in Informal Science Learning. Panel discussion with participant breakout sessions at the Association of Science and Technology Centers (ASTC) Annual Meeting (Sept 2022) (updated on 12/30)

- Exploring Authenticity in Informal Learning: Findings from a review of research and an examination of implications for practice. Invited practitioner workshop for Southern California practitioners (education, exhibit design, curators), featuring discussion of Authenticity project findings and exploration of how these might be applied to practice. Half-day workshop held at the Columbia Memorial Space Center, Downey, CA (Feb 2023) (updated on 12/30)

Coming Soon.

Credits

This project made possible via funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Advancing Informal Science Learning (AISL) program (Award #1906889).

Project Team

- Dr. Jim Kisiel (PI), Professor of Science Education, California State University, Long Beach

- Dr. Martin Storksdieck (Co-PI), Director, STEM Research Center, Oregon State University

- Kimberly Preston, Researcher, STEM Research Center, Oregon State University

- Kathleen Westervelt, Graduate Student Researcher, California State University, Long Beach

- Dr. Shawn Rowe, Oregon State University

Graduate Student Assistants, CSU Long Beach

- Zoe Allen

- Janel Ancayan

- Alyssa Bjorkquist

- Justin Fournier

- Rick O'Connor

- Maira Rodriguez

- Jerren Smith

- Nikki Wyrick

Librarian, CSU Long Beach

- Norah DeBellis

Webpage

- Seth Meyer

Project Advisors

- Andee Rubin

- Dr. Jessica Luke

- Dr. Margaret Evans