Fall 2022 Archived Research @ the Beach Newsletter

Research @ the Beach

Each semester, this online publication is produced to recognize faculty and students for their work. Our Fall 2022 issue of Research @ the Beach provides an overview of new awards / proposals / research expenditures for the 2021-2022 fiscal year, highlights ongoing faculty research related to climate change, and recognizes new external grant funding. In this issue:

Explore Laurie Huning’s research on unprecedented extreme climate events (i.e. floods + droughts) and their impacts on the environment; Dede Long’s efforts to improve the economic and environmental outcomes of governmental policies and private incentives; and Hojong Shin’s scholastic look into environmental reputation and bank liquidity under climate change risk.

You can also discover how Bengt Allen is protecting the ocean / coastal wetlands; Kent Hayward is making film production more environmentally sustainable; David Hedden is integrating methods of food sustainability with a design-thinking perspective; and Tom O’Brien is conducting trade and transportation research as the Executive Director of the Center for International Trade and Transportation.

More information can be accessed by clicking the topics below.

July 1, 2021 - June 30th, 2022

| Total # of New Proposals Submitted | Total New Research $ Requested | Total # New Proposals Awarded | Total New Research $ Awarded | Research Expenditures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 280 |

$104,014,213 | 186 | $65,777,404 | $33,857,783.80 |

By Laurie Huning, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Civil Engineering and Construction Engineering Management

College of Engineering

Climate Change and Extreme Events

As global temperatures rise, anthropogenic climate change enhances the terrestrial water cycle. The intensification of the global water cycle is anticipated to increase the frequency, persistence, and severity of extreme events such as droughts and floods across many parts of the world. This can contribute to a region experiencing extreme events, having larger magnitudes, and more severe impacts than were not previously encountered across the area in the past. Floods and droughts can have significant societal impacts and lead to severe economic losses annually across the globe. These extreme events pose challenges for existing natural and built systems such as critical infrastructure and lifeline systems. Studies also suggest that wet regions are becoming wetter, while dry regions are becoming drier.

In light of observed changes and future projections related to extreme events and natural hazards, we must better understand lessons from past floods and droughts and learn from the steps that people have taken to mitigate their impacts. In addition, we need to explore how to better manage and prepare for the risks associated with climate change-fueled extremes if they have never been experienced in a region before.

Synthesis of Extreme Events and Insights into Risk Reduction Strategies

Dr. Laurie Huning was part of an international team of researchers who recently published a study in Nature, which investigates challenges associated with unprecedented extreme events. Specifically, the team gathered data on paired events or two successive droughts or flood events occurring at the same locations to develop a unique global database of 45 paired events. They studied droughts and floods across regions with a variety of socioeconomic, hydrologic, and climatic conditions spanning North and South America, Europe, Australia, Asia, and Africa to investigate risk management worldwide.

While the researchers found that risk management often helps to reduce the impacts of droughts and floods, their synthesis also revealed that it is challenging to reduce the impact of extreme events with magnitudes that had not affected the region in the past. One reason is that existing infrastructure is typically designed for extreme events of a given magnitude and associated return period (e.g., a 100-year return period). As an example, the “100-year flood” corresponds to an event with a 1% chance of occurrence during any given year, or in other words, an event where the expected time between occurrences of its magnitude or larger is, on average, once every 100 years. However, with climate change fueling more extreme events, the future 100-year event may have a larger magnitude than estimated from the historical record for a given location.

Of the paired events examined, results also indicated that the impacts of the second event tended to be more detrimental than the first when the event was of a larger magnitude; however, some success stories were found for paired flood events. The impact of the second hazard was lower despite being a more hazardous event in some cases when effective risk and emergency management, improved early warning and real-time monitoring systems, and large and/or increased investments in both structural and non-structural approaches were harnessed and integrated together.

Our global community must still improve our management and preparation for unprecedented events since they are projected to occur in a warming global climate. Engineering design, policy, and planning should account for climate change to ensure that more sustainable, resilient, and effective mitigation strategies are employed. Advancements needed to prepare for extreme events and translate science into action should not be considered isolated activities, but rather often interdisciplinary in nature. They therefore require synergistic efforts across multiple fields and sectors.

Reference:

Kreibich et al. (2022), The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management, Nature, 608, 80-86, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04917-5.

By Dede Long, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Economics

College of Liberal Arts

Environmental Economics

Growing up in a tiny, heavily polluted industrial town in China where air often had a pungent sharp odor, I have always hoped to solve environmental problems someday when I grow up. This childhood dream has nurtured my interest in environmental economics and eventually turned into long-term professional aspirations of becoming a scholar and an educator advocating environmental issues.

As a researcher working in the realm of environmental economics, I aspire to make new contributions to the field and to solve complex environmental problems by continuing to advance my skills and expertise. Given the multi-faceted nature of environmental issues, I strive to sharpen my leadership, organizational, and communication skills to pursue new multidisciplinary collaboration opportunities and make a lasting impact in the field.

My research efforts have focused on improving the economic and environmental outcomes of governmental policies and private incentives used to promote ecosystem services provision and to flight challenges imposed by climate change and global warming.Nature has constantly provided us with critical environmental assets such as soil erosion control and air purification. However, many of these services are greatly undervalued due to a lack of observable prices. Without policies or incentives, individuals are often not motivated to improve the environment because benefits largely accrue to others. This collective action dilemma is also what prevents us from making progress combating climate change and global warming.

Under the broad agenda, I am particularly interested in two interrelated themes. The first is to understand how the public values environmental goods and ecosystem services. To that end, my recent projects have investigated the public’s demand for improvements in environmental amenities. Specifically, I examined how urban greenspace affect local communities’ health outcomes and how urban community gardens alleviate food insecurity problems among low-income communities.

The second theme of my research is to investigate how to promote private citizens and entities to provide environmental public goods and thus fight climate crisis. I leveraged techniques in behavioral and experimental economics, conducting field and laboratory experiments to analyze how information and framing treatment influence people’s willingness to donate to deforestation prevention and carbon emissions reduction programs. When top-down policies are not effective given the environmental good’s public-good nature, voluntary actions at the individual level are crucial to achieving environmental protection goals. As a result. learning how to effectively and efficiently incentivize individual voluntary actions is important.

My studies demonstrate how contextual factors affect consumer behaviors to address climate change issues. More importantly, as demonstrated in a large body of literature, information may be interpreted differently by groups with different pre-existing beliefs, leading to increasing divergence in public opinions and growing skepticism regarding environmental issues like climate change. My studies help understand how information interacts with people’s beliefs and therefore their actions.

By Hojong Shin Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Finance

College of Business

Environmental Reputation and Bank Liquidity Under Climate Change Risk

As climate change poses new threats to the global economy, bank management of reputational risks for ESG (Environment, Social, and Governance) issues has received increased attention from practitioners as well as regulators. For example, the Bank for International Settlements highlighted how incorporating climate-related risks into financial risk monitoring is challenging but critical to preserving long-term global financial stability. [1] In consultation with Credit Suisse and KPMG, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) released an analytical report that focuses on potential channels through which banks’ ESG risks affect bank performance and stability.[2] Yet, despite the growing importance of environment-related ESG issues along with climate change risks for banking sector fragility, the specific channels between environment-related bank ESG practices and financial stability are underexplored.

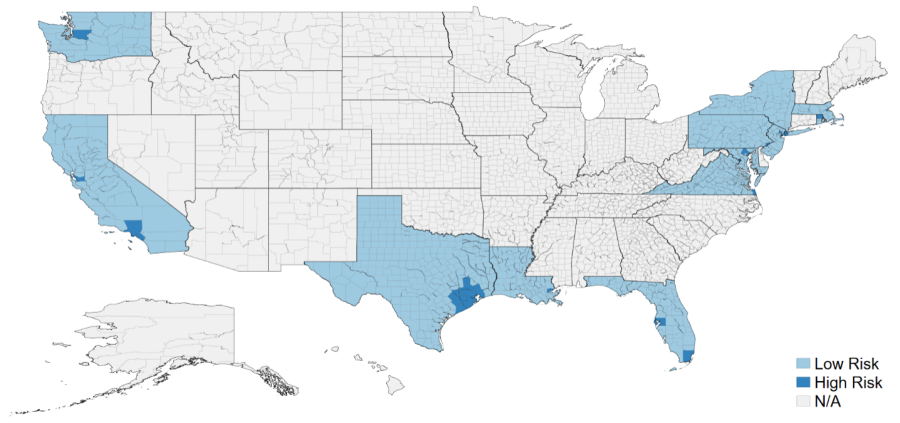

In our paper, we focus on the behaviors of bank depositors as a channel through which environment related ESG risks trigger banks’ fragility in markets exposed to severe climate change. In this study, if a city’s expected mean annual loss from a 40-cm rise of sea level is higher than 0.01% of its annual GDP, the city is assumed to have severe climate change risk. Next, we define each county that contains these qualifying cities as a county exposed to severe climate change risk. As you see the table and the figure in the below, Long Beach is one of the US cities exposed to severe climate change risks. Thus, this study directly impacts our Long Beach community.

Our study finds that banks with a poor reputation on environmental issues are more likely to experience declined local deposits in the regions exposed to severe climate change risks. Those banks with poor reputations on environmental issues are also expected to reduce their mortgage origination in the regions with severe climate change risks. Further, the banks with high environmental reputational risks are expected to diminish their overall liquidity creation if those banks have greater exposure to the regions with severe climate risks in terms of their deposit shares in the regions. Consequently, banks with high deposit shares in regions exposed to severe climate change risks should strengthen their management of local deposit drawdown by relocating their branches out of the regions with severe climate change risks or managing the banks’ environmental reputational risk. From those outcomes, we can conclude that a bank’s reputational risk for environmental issues is one of the key factors that leads to a drawdown of local deposits, which have negative effects on their local credit provision in their area.

Table: List of US counties exposed to severe climate change risks

|

City (State) |

County |

Climate change risk |

|---|---|---|

|

New Orleans (LA) |

Orleans Parish |

1.479 |

|

Miami (FL) |

Miami-Dade |

0.42 |

|

Tampa, St. Petersburg (FL) |

Hillsborough, Pinellas |

0.324 |

|

Virginia Beach (VA) |

Virginia Beach |

0.173 |

|

Boston (MA) |

Suffolk |

0.149 |

|

Baltimore (MD) |

Baltimore |

0.104 |

|

LA, Long Beach, Santa Ana (CA) |

Los Angeles, Orange |

0.097 |

|

New York (NY), Newark (NJ) |

Bronx, Kings, New York, Queens, Richmond, Essex |

0.089 |

|

Providence (RI) |

Providence |

0.083 |

|

Philadelphia (PA) |

Philadelphia |

0.044 |

|

San Francisco, Oakland (CA) |

San Francisco, Alameda |

0.042 |

|

Houston (TX) |

Walker, Montgomery, Liberty, Waller, Austin, Harris, Chambers, Colorado, Wharton, Fort Bend, Galveston, Brazoria, Matagorda |

0.038 |

|

Seattle (WA) |

King |

0.023 |

|

Washington, D.C. |

Washington |

0.016 |

Figure: Counties that belong to states exposed to severe climate change risk

[1] See details from “The green swan: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change.” Available at www.bis.org/publ/othp31.pdf.

[2] See details from “Environmental, Social, and Governance Integration for Banks: A Guide to Implementation.” Available at wwf.panda.org/?226990.

By Bengt Allen Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Biological Sciences

College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics

Protecting the Ocean / Coastal Wetlands

How did you get interested in this research?

I grew up far from the ocean and never really spent much time at the beach as a kid. When I was in high school, I got certified as a SCUBA diver before going on a trip. Pretty much the first time I went underwater in the ocean and saw how many amazing plants and animals were down there, I knew I wanted to be a marine biologist. After college, I spent several years as a SCUBA instructor in the Bahamas before returning to graduate school. Since then, I have studied the ecology and evolution of marine organisms – essentially, trying to understand how their interactions with the physical environment and each other determine where and how they live.

Can you give a brief summary of your research and/or grants you have received?

My current research has two main elements:

First, I study how predicted changes in temperature and ocean carbon chemistry (so-called ocean acidification) over the next century are expected to affect the structure and function of ecological communities on rocky shores. By manipulating temperature and ocean pH conditions in the field and lab, my students and I have shown that ecological consequences of increasing environmental variability will be determined by complex species-specific relationships between temperature, pH, and food. In response to sub-lethal levels of stress, many organisms exhibit characteristic physiological changes that increase their tolerance to subsequent exposures. The activation of this “stress response” requires, however, a significant energetic investment. In addition to positive effects on survival, stress responses may lead to reduced growth or reproduction due to energetic trade-offs between competing life history traits. This research adds to our understanding of the potential implications of increasing physiological stress for population persistence and species interactions in the face of global climate change. This work has been funded by the National Science Foundation and the CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology.

Second, in collaboration with Drs. Christine Whitcraft and Christopher Lowe, also in Biological Sciences at CSULB, I study how incorporating ecological concepts into broader restoration policies may better protect coastal wetlands. Wetlands provide a variety of key ecosystem functions that include food web support, nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, and nursery habitat for many ecologically and economically important species. They are also among the ecosystems most vulnerable to human activity. In southern California, some 70% of vegetated coastal wetland area has been destroyed over the past 150 years and much of the remainder damaged by development, fragmentation, and urban runoff. Our research makes specific recommendations that resource managers can use to maximize the potential benefit of restoration policies and practices designed to accelerate the return of key species and associated ecological processes in damaged ecosystems. This work has been funded by the Montrose Settlements Restoration Program via the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, California Sea Grant, and the CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology.

How will your research impact the CSULB campus and/or wider community?

To date, these projects have involved 14 MS students and over 50 undergraduate researchers. Many of these students spent a summer doing field research on rocky shores or in local salt marshes. Given the importance of hands-on experiential learning in my own career, providing similar opportunities for students at CSULB has been a priority for me. I also use many of the data sets collected by students as the foundation for data science activities in the classes I teach.

By Kent Hayward

Associate Professor

Film and Electronic Arts Department

College of the Arts

"Green Filmmaking" - Making Film Production More Environmentally Sustainable

As a kid in Wisconsin, I made little clay-mation stop-motion movies with my brother and continued to make short films with friends as I went through high school and college. Some were good, some not so good--but no matter the content, we were scrappy filmmakers, using whatever we could find to make into a movie. After grad school at CalArts, I freelanced in the film industry in visual effects and editorial. I noticed that the bigger the movies, the more wasteful they seemed to be. I recall one big Hollywood franchise film where the company I worked for built these amazing sets and props, and after weeks of careful work creating and shooting, it all had to be dismantled, shipped, or thrown away in one wrap day. The production didn’t want to spend any more money than it had to on stage rental or storage after the shooting was done. Around the same time, I started teaching and I’d try to save used lighting expendables, props, and gear that was going in the trash to take to my film students. That’s when I began to think about how to incorporate green principles like reduce, reuse, recycle into the filmmaking process.

My research is in making film production more environmentally sustainable, starting at the student level.

Filmmaking can be a very wasteful process. The practice of reducing the carbon footprint of the filmmaking process is called sustainable production or green filmmaking. According to a study put together by the Sustainable Producers Alliance, Hollywood blockbusters have an average carbon footprint of about 3,300 metric tons. That’s the same as the mass of about 300 school buses.

People who care about the environment in the entertainment industry have steadily come together to form a coalition called the Sustainable Producers Alliance (SPA). As a teacher, I have found a like-minded group of film production teachers, and together, with mentorship from SPA, we started the Green Films School Alliance (GFSA) in 2021. Founding members include AFI (American Film Institute), CSULB, NYU, UCLA, USC and CalArts to name a few.

“The GFSA's membership now hails from seven US states and four countries across three continents. Nine member schools are on the Hollywood Reporter’s Top 25 Film Schools list for 2022, with eight of them ranked in the top 10. These committed schools join the effort to combat wasteful film production practices. By expanding the alliance's commitment to teaching sustainable production to a wider group of schools, they are one step closer to making ‘green production‘ a standard practice for all filmmakers.” (from the Green Film School Alliance press release on 11/1/2022).

One of the chief tools that we use to minimize the carbon footprint of a student film is called the Production Environmental Actions Checklist for young filmmakers (PEACHy). The PEACHy is a checklist tool that we adapted from the industry standard PEACH, modifying it for the methods of production that students use. From energy-efficient LED lights to reusable water bottles, from ride sharing to shooting locally, the checklist has many suggestions for reducing the carbon footprint of a film. PEACHy has been used by many student productions since we launched it, with around two dozen films garnering enough points on the checklist to earn an Environmental Media Association (EMA) Green Seal for Students.

In addition to the work on the GFSA, I have a book proposal submitted to Routledge/Focal Press on the subject of sustainability in student film productions. (Excerpt attached)

This month I’ve been working with a designer in the Sustainability Office to create a CSULB Green Seal for student films.

I’ve also presented talks on sustainability in student films for the University Film and Video Association, The Hollywood Climate Summit, and The Green Film School Alliance, and I recently had a proposal accepted to speak at a sustainability conference in Italy.

Creating the GFSA has been an exciting way to build a coalition for change and to build open-source best practices for sustainability in filmmaking. Writing a book and presenting at conferences has been great for sharing these ideas too. But it’s more than just getting the word out there.

The real work is in the daily practices during pre-production, production, and post-production. This year I am personally working with select student crews to track their films’ footprints. Participating productions designate a Sustainability Coordinator and check in with each department (camera, wardrobe, food service, set construction, etc.) before and after shooting, tracking progress with PEACHy. If they score high enough, they earn a green seal for their credits. By standardizing the production workflow to include sustainability as a normal part of filmmaking, we’ve created change in all the future films these students will work on too.

I tell my students that it IS easy being green in filmmaking, you just have to put a bit of work into it. It’s all about making film production more efficient, less costly, and better for everyone. Movies have the power to influence and change-- in content, and in the whole process of production. Our film students have the potential to change the world, one movie at a time.

Excerpt from proposed book “Sustainability in Student Film Production” Routledge/Focal Press

“Pre-Production: The Plan”

“I love it when a plan comes together!” Hannibal Smith, The A-Team

Pre-production is where we make our brilliant, cunning, and sneaky plan, like Wiley Coyote at the drawing board or Dr. Olivia Octavius in the Spider-verse. Whether it’s an improvised slingshot or a multi-dimensional supercollider, the plan is critical. That’s where we begin to think about our footprint.

Making the plan

Pre-production planning is hands-down the most important stage of production, and it’s always the area that filmmakers wish they had spent more time on. Find your collaborators, assemble the team, establish regular production meetings, and make a sustainability plan part of your prep. In the same way that you make a financial plan to pay for the movie, and do a visual plan or look book for the cinematography of your project, you need to establish your sustainability strategy. Will you go for a Guinness World Record in sustainability? How much can you realistically tackle? Can you achieve a “green seal” for your credits? Which one? Is it going to be a huge battle just to get the team to recycle their aluminium cans and turn off the lights at night? The one thing that is certain is that you have the ability to make a difference; how much of a difference is what we plan for in pre-production. One proven strategy is to bring someone onto your team as a sustainability coordinator.

Bringing on a Sustainability Coordinator

The person who does the legwork on your green filmmaking plan is your Sustainability Coordinator. On a big studio project for Disney or Warner Brothers, for example, the studio might have several people on the case: a Director of Sustainability, a Sustainability Coordinator, and/or an Eco PA. A Director of Sustainability-typerole oversees the sustainability efforts across their slate, on the multitude of projects (TV shows, movies, etc) that a studio might be working on simultaneously at any given time. Further, they might supervise an in-house department and dedicated Sustainability Coordinators on each show. A larger project might also have additional Sustainability PA’s; the company may havea Sustainability Internship. The staff and titles of people working on sustainability will be different for each project depending on the company, size, budget, resources, and environmental mission but all the major content producers, specifically members of the Sustainable Production Alliance, address sustainable production on their shows in one way or another.

For a student production – and for our purposes here - you might call this person a Sustainability Coordinator, but you can call them whatever you want to… Green Film Coordinator, Eco Czar, Sustainability Overlord, Benevolent Eco-Princess, whatever makes sense for you and your team. Not every production has a sustainability person, of course, but it’s a good idea to have a dedicated person to follow up on all the ways that the whole crew can participate in making the film “green.” If you don't have the space or the budget to feed this extra mouth, consider upgrading a PA role to Sustainability Coordinator. They can still help with general PA tasks while also managing the set's sustainability practices - and may be more likely to work for free when receiving a better credit for their resume. Identify yoursustainability person and get them involved early.

By David Hedden

Lecturer

Department of Design

College of the Arts

The Dilemma of Food as a Commodity

As an industrial designer/product designer, and a lifelong advocate of the environment, I have tried to integrate methods of sustainability into my design practice. A product's lifecycle with relation to the ecosystems and the resources needed to produce and distribute the product often align more with short term sales goals than long term ecological and community goals. This dissonance has led me to explore systems of mutualistic symbiosis that benefit the triple bottom line, as opposed to parasitic consumption and perpetual obsolescence. After searching far and wide for the most, and least, sustainable products, I realized that the “product” of food, and the industrialized food systems that grow and distribute the majority of food, have the most potential to create a positive impact if approached from a design-thinking perspective.

MY ECO-PIPHANY

With this “eco-piphany,” I decided to realign my design practice towards developing, testing, and educating about sustainable food systems. These systems are generally case specific and use a combination of advanced and historical agricultural practices to produce a product lifecycle with the highest quality product and least environmental impact, and often have other peripheral benefits. Apples to apples, these sustainable foods reduce food-miles, conserve water and resources, build topsoil, sequester carbon, don’t pollute downstream, reduce food waste in production and distribution, are less impacted by seasonal variation or climate extremes, provide better quality nutrition, encourage biodiversity, and benefit local communities, their economies and their environment.

FIRST FORAYS INTO SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

My research has taken on this challenge through many iterations of prototyping, testing, refinement, expansion, and has evolved most through collaboration and applying a design-thinking approach. My first prototypes were to test the feasibility of farming on underutilized space by testing systems on the roof of my apartment not far from CSULB. I found that even non-traditional farming spaces that are in urban areas can produce a significant amount of food with the most minimal food-miles created. Arable soil is great to grow plants in when available, but in a city the price point for land, water, and power is not very favorable for a traditional farmer. Soil-less alternatives, and soil-hybrid systems, allow for vertical farming and a more precise integration of three dimensional growing space which can increase output significantly compared to traditional two dimensional farming. These 3D growing spaces can take advantage of underutilized space, like rooftops, walls and borders, vacant lots and warehouses, and even be applied modularly in shipping container based systems.

HERE FISHY, FISHY - EXPERIMENTING WITH AQUAPONICS

I expanded my research to explore hydroponics and aquaponics and successfully ran a prototype system for 1 year with an urban agriculture incubator program in North Long Beach. I then consulted on a grant to design and build the 1,000 square foot vertical aquaponics system for the Growing Experience Urban Farm in 2013. This system has been running for 9 years now and is consistently producing Tilapia and high quality basil to local restaurants and chefs. Aquaponic systems use just a fraction of the water and resources that are used in traditional farming methods and vertical farming allows for maximum production per square foot. Aquaponic and hydroponic recirculating systems using precision application of nutrients to allow for minimal water and nutrient loss compared to the high rate of loss to runoff and evaporation of traditional farms.

GIVE PEAS A CHANCE - LB’S FIRST PUBLIC EDIBLE LANDSCAPE

My research also included designing and building the open-access community garden on a vacant lot in front of the Michelle Obama Library in North Long Beach which featured water conserving drip systems and a “take what you need, leave some for your neighbor” approach to food access.

GETTING TO GROW WITH LB’S CAMBODIAN COMMUNITY

Most recently I was appointed Director of Agriculture for the MAYE Center (Meditation, Agriculture, Yoga, Education) to continue and expand upon their existing garden therapy, education, and community wellness programs.

MEANWHILE, BACK ON THE FARM…

And in this past year we have joined in partnership with the County of Los Angeles Housing Authority to prevent the 7.5 acre Growing Experience Urban Farm from being bulldozed, as well as implement and expand upon the resources and programs previously offered at this farm. Through this opportunity we are starting the dialogue of how housing and urban agriculture can be integrated for greater community wellness. We are also showing a collaborative approach that is unique to an urban farm with the variety of partners we work with and the mutual benefit approach each partner shares within the shared space.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER: FOOD AS A PROMPT FOR EDUCATION & DESIGN

The projects that we are researching and deploying are serving the Long Beach and CSULB community with access to sustainability, health, and wellness in a variety of ways. We are implementing workforce development programs to provide paid internships, job training, and other job related experience. We are currently collaborating with CSULB and LBCC departments to provide internships and service learning opportunities, currently within the fields of Design, Art, Environmental Science and Policy, Chemistry, and Geography, and looking to find more ways to collaborate with other programs in this space. We hosted a STEAM summer camp with the Long Beach Public Library this past summer. The UC Extensions Master Gardener network and its many volunteers are consistent participants. We are implementing drone training for agriculture, environmental monitoring, solar, utility, and other industry related jobs. We have programs working with local food distribution organizations to reclaim and redistribute food that would go to waste, and then we are composting at a community scale what does go to waste. Our community scale composting reduces climate changing emissions and recycles the nutrient rich resource into fertile soil that is shared back to the community. We are carbon farming with soil building techniques such as no-tilling, using cover crops, and innovative mulching of landscaping waste that would otherwise go into landfills. I have found that it is often the most bio-diverse systems that are also the most resilient. It is this inspiration that we seek a diversity of collaboration and creativity to nurture this dynamic work. Through sustainable food systems we cultivate health and wellness, for the individual, the environment, and the community.

By Tom O'Brien Ph.D.

Executive Director - Center for International Trade and Transportation

College of Professional and Continuing Education

Trade & Transportation Research

I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Morocco in the late 1980s, serving as a high school teacher and curriculum developer. During one of my summer projects away from the classroom, I had an opportunity to work with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) on a project seeking to untangle competing pre- and post-Colonial ownership claims for land. These competing claims created a host of challenges for the country including raising obstacles to the restoration of deteriorating structures in the old medinas. This was my introduction to the complexity of issues surrounding urban development and I was fascinated. When I left Morocco, I landed in Southern California to pursue a Masters degree and then a Ph.D. in urban planning.

I have always been interested in the institutional issues that often hinder good urban management; and at USC I was able to see these issues at play in everything from the development of the regional public transit system to the response to the Rodney King verdicts. An assignment as a research assistant sent me to Long Beach to document a public hearing on the nation’s freight-related infrastructure needs. I’ve never left.

I started as the Center for International Trade and Transportation’s (CITT) Applied Research Coordinator, then its Director of Research and finally Executive Director. We play a unique role on the CSULB campus. As a partner to a number of other universities through the METRANS Transportation Consortium, we conduct our own research in the area of trade and transportation. We also help to fund the work of faculty members at CSULB. As a unit of the College of Continuing and Professional Education (CPaCE), we are also committed to workforce and professional development and continuing education, including the now 25-year old Global Logistics Professional program.

My own research builds upon my interest in institutions. I have done extensive work on the role played by equipment management, including chassis, in fluid supply chains. More recently, I have been working with CITT’s Director of Research and Workforce Development Tyler Reeb, and Seiji Steimetz and Robert Kleinhenz from Economics on a study of the impacts on the port workforce of the State’s zero emissions mandates for cargo handling equipment.

I am proud of the impact of our work on our campus, the trade and transportation industry and the community. We are building a talent pipeline as partners with the Port of Long Beach and Long Beach Unified School District in the Academy of Global Logistics at Cabrillo High School. We assisted the Governor’s Office in convening key supply chain stakeholders in order to address the challenges to the nation’s supply chains as a result of the pandemic. We also play an important role introducing students at CSULB to trade and transportation as a possible career pathway and area of study and research. At any given time, we employ up to ten students at the undergraduate and graduate level from all disciplines. They are evidence of the strong pool of talent CSULB offers to all sectors of the regional economy.

|

Faculty Name |

Funding Agency | Amount Awarded | Project Title | College/Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamiar Alaei | Office of National Coordinator for HIT (ONC) - DHHS | $232,750 | The PHIT Workforce Development Program | CHHS | |

| Kamiar Alaei | IREX via U.S. Dept of State | $85,425 | To enhance the capacity & quality of nursing & public health programs of Tel Afar (Telafar) University to provide educational and support opportunities to affected population | CHHS | |

| Pitiporn Asvapathanagul | U.S. Department of Education | $1,572,334 | ASCEND: AANAPI Student Success CENter & Development | COE | |

| Perla Ayala | NIH - NIGMS | $147,500 | Engineering Biomimetic Tissues for Muscle Repair | COE | |

| Paul Baker Prindle | Arts Council for Long Beach | $1,000 | Sol Negro 2022 Community Project Grant | COTA | |

| Andrea Balbas | NSF | $138,534 | Collaborative Research: Investigating Mantle Source Reservoirs and Cretaceous Plate Motions Recorded by Ancient Mid-Pacific Oceanic Rises and Seamount Tracks | CNSM | |

| Andrea Balbas | NSF | $101,668 | Collaborative Research: Investigating Mantle Source Reservoirs and Cretaceous Plate Motions Recorded by Ancient Mid-Pacific Oceanic Rises and Seamount Tracks | CNSM | |

| Ehsan Barjasteh | NSF | $969,532 | An Active Learning-based Educational Program for Hispanic STEM Students through Industry-University Partnership | COE | |

| Joanna Barreras | Emory University via NIH | $18,333 | Center for AI OS Research at Emory University | CHHS | |

| Erin Booth-Caro | Justice Corps | $29,400 | Justice Corps | SA | |

| Judy Brusslan | NIH - NIGMS | $460,724 | Bridges to the Doctorate Research Training Program at California State University Long Beach | CNSM | |

| Rebecca Bustamante | Trustees of the California State University via Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | $173,855 | Center for Transformational Educator Preparation (CTEPP) Award CSULB-CED Cultivating Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Teacher Preparation in Field Practice | CED | |

| Shailesh Chandra | California Department of Transportation | $144,000 | Innovation Tools and Concept Strategies for System Planning | COE | |

| Brian Coriaty | Department of Parks and Recreation | $31,561 | 2021-2022 Aquatic Center Grant | SA | |

| Laura D'Anna | UC Office of the President (UCOP) | $747,765 | Is Marijuana the new menthol? Can marijuana use among YBM serve as a hook for nicotine addiction? | CHHS | |

| Laura D'Anna | NIH - NIGMS | $403,709 | CHER Institute II: Community-engaged behavioral and biomedical research training for early career faculty | CHHS | |

| Shelley Eriksen | California Governor's Office of Emergency Services (CAL OES) | $103,119 | Campus Sexual Assault Program | CLA | |

| Melawhy Garcia-Vega | Unidos US | $149,998 | Comprando Rico y Sano | CHHS | |

| Gerry Hanley | Tennesse State University via NSF | $145,500 | Scaling Affordable Learning Solutions with Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Phase 3 | CLA | |

| Raisa Hernandez-Pacheco | NSF | $46,000 | Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP)-Alexis Diaz | CNSM | |

| Raisa Hernandez-Pacheco | NSF | $452, 989 | BRC-BIO: The evolutionary demography of a social mammal | CNSM | |

| Raisa Hernandez-Pacheco | NIH - NGMS | $181,133 | Modeling Health Histories and the Dynamics of Social Inequality in a Nonhuman Primate Population | CNSM | |

| Erika Holland | USC (NOAA) | $21,059 | Microplastic Fiber Toxicity in Marine Species with Different Feeding Types | CNSM | |

| Lily House-Peters | Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research | $150,000 | Developing Training Materials on Transdisciplinary Science related to Global Environmental Change in the Americas | CLA | |

| Lucy Huckabay | CA Department of Health Care Access and Information | $144,000 | Song Brown FNP | CHHS | |

| Prashanth Jaikumar | NSF | $35,676 | RUI: Neutron Star Oscillations as Probes of Dense Matter Properties and Phases | CNSM | |

| Amber Johnson | City of Long Beach via NIH | $100,000 | Black Health Equity Collaborative | CHHS | |

| Kenneth Kelly | Chico State Enterprise via USDA | $85,089 | Cal Fresh Outreach | SA | |

| Kenneth Kelly | Chico State Enterprise via USDA | $22,439 | Basic Needs | SA | |

| James Kiesel | NSF | $505,863 | The Expansion of a Mobile Making Project That Engages Underserved Youth Across California in STEM | CNSM | |

| Megan Kline Crockett | Arts Council for Long Beach | $4,000 | Classroom Connections | COTA | |

| Heather Macias | NSF | $68,822 | Collaborative Research: Broadening Inclusive Participation in Artificial Intelligence Undergraduate Education for Social Good Using a Situated Learning Approach | CED | |

| Aili Malm | Arizona Board of Regents for and on behalf of Arizona State University via DOJ | $75,438 | Supporting small and rural law enforcement agency body-worn camera policy and implementation program | CHHS | |

| Janette Mariscal | U.S. Department of Education | $1,309,440 | TRIO-Ronal E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program | SA | |

| Ron Mark | Commission on POST | $668,581 | POST Use of Force (UOF) Force Options De-escalation Train-the-Trainer Course | CHHS | |

| Ron Mark | Commission on POST | $2,633,961 | Sherman Block Supervisory Leadership Institute | CHHS | |

| Ron Mark | Commission on POST | $391,265 | POST Executive Development Course | CHHS | |

| Ron Mark | Commission on POST | $593,638 | POST Management Course | CHHS | |

| Wade Martin | Downtown Long Beach Associate (DLBA) | $9,944 | Entrepreneur and Small Business Education Series 2022 | AA | |

| Wade Martin | Sunstone Management Inc. | $75,000 | Accelerator Proposal | AA | |

| Stephen Mezyk | NSF | $192,385 | Collaborative Research: CAS-MNP: Radical-induced Weathering of Micro- and Nanoplastics in Water: Impacts on Suspensions, Agglomerations, and Contaminant Adsorptions | CNSM | |

| Thomas O'Brien | USC via U.S. Dept. of Transportation | $39,528 | METRANS University Transportation Center | CPIE | |

| Hung Nguyen | Charitable Ventures | $100,000 | Orange County Sustainability Decathlon (OCSD) | COE | |

| Sandra Perez | Cal State San Bernardino University Enterprises Corporation via US Dept of Education | $14,705 | Evaluation: Certificate Program in Criminal Justice Spanish | AA | |

| Samiha Rahman | Arizona State University Foundation via Spencer Foundation | $14,909 | Black Muslim Worldmaking: Race, Religion, and Gender in the Lives of Black Muslim College Students | CHHS | |

| Tyler Reeb | National Indian Justice Center, Inc via California Energy Commission | $287,841 | IDEAL ZEV Workforce Pilot | CPaCE | |

| Peter Ramirez | Epirus, Inc. (NSF) | $24,751 | Antiviral Electromagnetic Pulses (Covid-19) | CNSM | |

| Curglin Robertson | U.S. Department of Education | $658,888 | Upward Bound Program I (Long Beach and Paramount) | SA | |

| Curglin Robertson | U.S. Department of Education | $366,048 | Upward Bound Program I (Compton and Gardena) | SA | |

| Shadi Saadeh | The Regents of the University of California via SJSU via State of CA | $17,478 | City and Council Pavement Improvement Center (CCPIC) | COE | |

| Susan Salas | Via Care Community Health Center via Ca Dept. of Health Care Services | $13,310 | Via Care Mentored Internship Program | CHHS | |

| Kelli Sanderson | U.S. Department of Education | $1,250,000 | Culturally Responsive Instruction and Intervention in Self-Determination Program (CRISP) | CED | |

| Dominica Scibetta | U.S. Department of Education | $2,450,800 | California State University Long Beach GEAR UP Program | SA | |

| Antonella Sciortino | UC Office of the President (UCOP) | $100,000 | MESA University Program | COE | |

| Antonella Sciortino | UC Office of the President (UCOP) | $103,106 | MESA College Prep Program | COE | |

| Karyn Scissum Gunn | NSF | $1,000,000 | ADVANCE Adaptation: Innovating Faculty Workloads through an Equity Lens | AA | |

| Michele Scott | U.S. Department of Education | $1,368,965 | CSULB Educational Opportunity Center Program | SA | |

| Seiji Steimetz | Long Beach Economic Partnership | $50,000 | Economic Impact of Advanced Air Mobility on Southern California | CLA | |

| Kagba Suaray | Mathematical Association of America | $4,185 | MAA Tensor-SUMNA Program - Hesabu Circle | CNSM | |

| Roy Surajit | Southern California Gas Company | $22,500 | Efficient Production and Safe Transmission Of Green Hydrogen | COE | |

| Fangyuan Tian | NIH - NIGMS | $110,625 | Porous inorganic Framework Thin Film as Drug-Eluting Stent Coating | CNSM | |

| Rafael Topete | Los Angeles County Office of Education | $20,000 | LACOE - CAMP Intern Program | SA | |

| Jelena Trajkovic | The Regents of the University of California Berkeley via CA OPR | $43,010 | A's for All: Scaling the Success of Proficiency-Based Learning | COE | |

| Yada Treesukosol | NIH - NIGMS | $147,393 | Physiological mechanisms underlying alterations in diet preference | CLA | |

| Guido Urizar | NIH - NIGMS | $147,460 | Intergenerational Effects of Stress among Low-Income Pregnant Mothers and their Infants | CLA | |

| Daniel Whisler | U.S. Army | $441,000 | Enhancing Material Testing and Characterization by the Long Beach Engineering Center | COE | |

| Christine Whitcraft | Southwest Wetlands Interpretive Association (SWIA) | $12,271 | Assessing the effects of sediment augmentation and active planting at the Seal Beach wetland | CNSM | |

| Yu Yang | NSF | $96,171 | RUI: Global Optimization of Chance-Constrained Programming for Reliable Process Design | COE | |

| Yu Yang | Southern California Gas Company | $22,500 | Efficient Production and Safe Transmission Of Green Hydrogen | COE | |

| Henry Yeh | California Energy Commission | $499,908 | ZEV Training Program for Communities and Business | COE | |

| Saba Yohannes-Reda | Paramount Unified School District | $25,000 | PUSD MESA College Prep Program | COE | |

| Amanda Young | U.S. Department of Education | $1,250,000 | Project CAPE (Certification in Adapted Physical Education) | CHHS | |

| Amanda Young | U.S. Department of Education | $250,000 | Project CAPE (Certification in Adapted Physical Education) | CHHS |