Hands-on clinic gives CSULB students first real taste of healing

Marcos De La Cruz grips a yellow paddle in his right hand and flips it from side to side, mimicking the motions of cleaning a litter box. For most people, this would be mundane. For him, it’s a milestone.

In 2017, an aneurysm-induced stroke took nearly everything from De La Cruz — his mobility, his independence, his sense of identity. But with help from the students at CSULB’s Neuro Pro Bono Clinic, he’s slowly reclaiming it, one carefully coached movement at a time.

“You have to do something a thousand times before it gets easier,” he says with barely a trace of the aphasia that stole his speech for nearly a year. “I tell people, I’m more stubborn than my stroke.”

For 15 years, the Neuro Clinic, which operates out of a newly remodeled lab within the College of Health and Human Services, has provided free physical therapy to individuals recovering from neurological disorders — strokes, brain injuries, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Most are uninsured or “Medi-Cal pending,” explains clinic director Dr. Kristin DeMars, a board-certified neurologic clinical specialist and full-time faculty member in CSULB’s Department of Physical Therapy.

“They may have a stroke, but they don’t have insurance — and it can take several weeks to months before they qualify,” she says. Or, as happens far more often, patients have exhausted their benefits but still show potential for progress.

That’s where the clinic steps in — and so do the students.

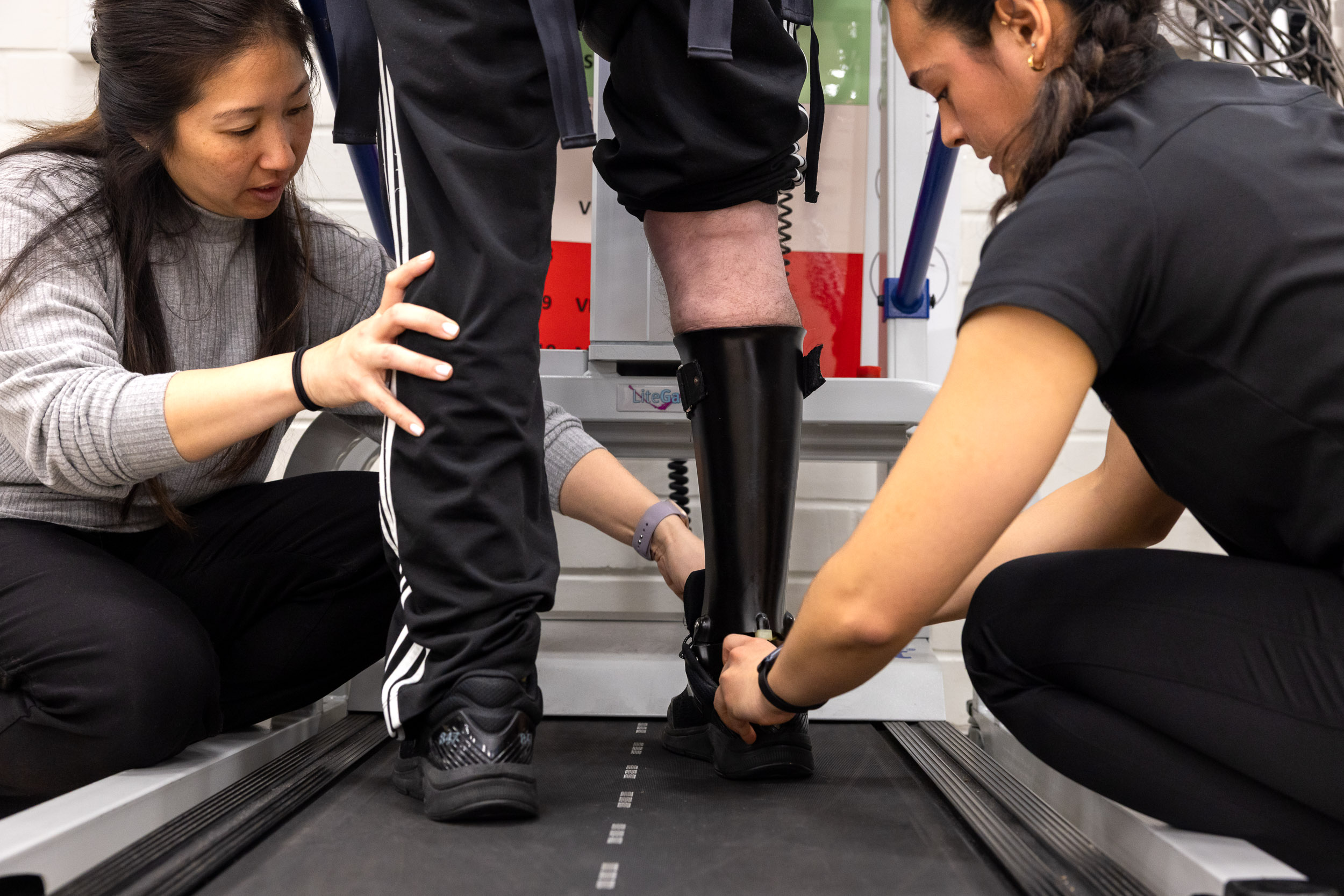

Each semester, 36 second-year Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students work in the clinic under expert supervision. It’s the first exposure they have to patient care, and it’s a powerful one.

On this day, student Romina Silva is working with a stroke survivor named Howard Leist. It’s his first time attending the clinic, and he’s already making progress, just six weeks in.

“Howard is aphasic so he can’t fully express himself,” Silva said, “but Howard’s wife was just saying that his motivation levels have increased, and he's super focused on getting better.”

Like all Neuro Clinic patients, Leist showed up with unique limitations and goals.

“He has weak quadriceps, weak hip flexors and then he lacks a little bit of selective motor control,” Silva explains. “So those are kind of the big things that we are focusing on.”

With expert faculty just steps away, Silva is beginning to apply what she’s learned in class — with weekly sessions that involve strength training, treadmill work, electrical stimulation and manual resistance.

“Neuro Clinic is like that first taste of what we're going to be doing,” she said. “It's the chance for us to kind of start developing that clinician brain because up to now it's just been, like, student brain.”

One of the biggest lessons? Letting go of the need to be perfect.

“I came in having these high standards for myself,” Silva says, “feeling like I need to perform at my best at all times and feeling very hard on myself when I was probably performing perfectly fine, just not meeting my standards.”

As it turns out, her patient is much the same.

“He's very hard on himself,” she says of Leist. He wants to do well and so, at times, he gets frustrated during our sessions. I have to be the one to tell him, ‘No, you're doing really well! These are all the things that you're improving ...’”

In teaching Leist to see his own strengths, Silva is learning them for herself.

“I’m focusing more on the process of becoming a clinician, and growing, and knowing that you don't have to be the best clinician possible for your patient or know all the [answers]. It’s really the relationship that you form with your patient.”

De La Cruz emphatically agrees. Now in his seventh year at the clinic, he has worked with dozens of students.

“Every student I’ve had teaches me something,” he says, “and I teach them, too. I tell them, ‘Listen to your patients. You know the science, but I know my body. If we work together, it’s the best of both worlds.’”

He wasn't always this confident.

After a brain aneurysm caused his stroke at age 39, De La Cruz attended physical therapy at a professional rehab facility for the better part of a year. By the time his insurance ran out, he still needed a wheelchair — something he lamented. He was referred to CSULB and met with DeMars.

“I was so deflated,” he recalls. “I was like, ‘If the actual therapists didn’t help me, the students will not.’”

DeMars asked him to bend his right knee — the key to unlocking his ability to walk. Previous therapists had asked the same of him. No dice. So she changed tactics. Instead of trying to reason with the disconnected part of his brain that had forgotten how to move, she spoke to the part that still remembered how to play.

"Do you play soccer?" she asked him.

As it turned out, he was a longtime soccer fan.

She placed a ball in front of his wheelchair.

“Kick it,” she said.

And he did.

“After that, my point of view about this place changed.”

Today, De La Cruz walks without a wheelchair or cane. He showers and cooks for himself. He goes to the gym on his own. Each semester, he sets a new goal — something that once seemed out of reach, something real.

Right now, it’s about cleaning out the litter box — a chore his longtime girlfriend has asked him to start doing. More than a chore, the “scooping” motion he’s learning is a test of function and balance, strength and coordination. A small but complicated movement most people take for granted. The simulation involves repetition — the kind of repetition that leads to rewiring.

“I really think that this program is amazing,” he says. “I live in L.A. It took me an hour to get here today. There are programs closer to me, but I love this place.”

At the end of the session, De La Cruz checks his phone for his Uber driver’s location, then says goodbye and walks outside to wait. Asked what he would say to others considering the Neuro Clinic, he doesn’t hesitate.

“What are you waiting for? This is the best. Trust me.”