COVID-19 has unintended consequences for nurse practitioner's cancer patients

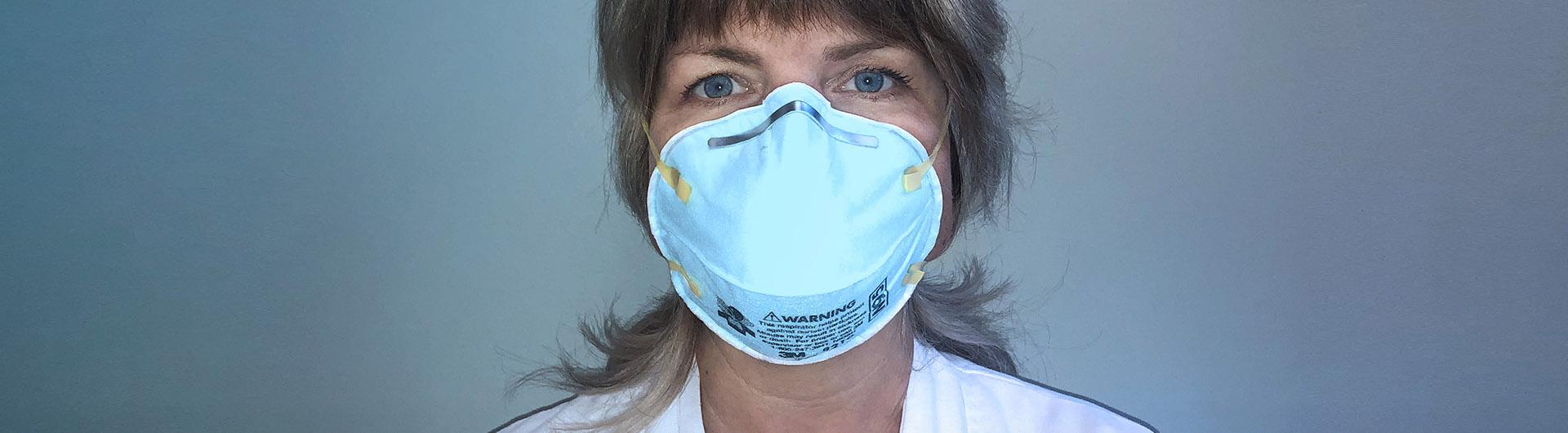

Nurse Practitioner Jamie Balderas geared up in her yellow protective gown, goggles and a face mask before she entered the room. Her patient, a 55-year-old man who came to the Todd Cancer Institute at Long Beach Memorial for his first chemotherapy treatment, had a fever. But was it COVID-19?

The Spanish-speaking patient didn’t say much as his son translated for him, Balderas said. She could see on his face that he was in pain, but he “didn’t want to complain.” With everyone wearing masks, it was hard to talk and translate, and showing compassion was difficult. The only way to express empathy to the patient and his family was through her tone of voice and her eyes.

She could feel the tension in the room as she drew the patient’s blood and assessed him, she said, deciding whether he should begin chemotherapy that day. His lungs sounded OK and he was not struggling to breathe, so she sent him home after his assessment to minimize the risk to himself and other patients.

A day later, the blood test results came in: he was septic and had an infection throughout his entire body. Balderas and her coworkers “took a deep sigh of relief” that it was not COVID-19, she said.

The patient was admitted to the hospital to avoid the risk of being exposed to the virus in the emergency room. There, doctors found a stent in his liver was blocked. They were able to treat him and three days later he was “a new person,” she said.

“The doctor called me and said ‘Jamie, you saved someone’s life.’ When he came back to start chemo, he was crying and thanking me,” she said. “I was so shaken up by that, because nurses make these decisions every day and it’s easy to second guess yourself. Am I being too over cautious? But he would have died if he hadn’t come to the infusion center that day.”

Balderas, who received her B.S. from the School of Nursing in 1996 and her Family Nurse Practitioner master’s degree in 2018, is among the Cal State Long Beach grads who face the coronavirus pandemic on a day-to-day basis. The effects of the virus extend well beyond emergency rooms, and Balderas said it has only added stress for her cancer patients who have compromised immune systems.

Working with cancer patients comes with a lot of “emotional baggage,” she said. Patients become like family, and nurses become bonded with their patients. Emotions run high with cancer patients as it is, and the coronavirus is just an additional stressor.

Balderas said the training and education she received from CSULB, coupled with her experience in the field, helps her diagnose and treat her patients and make decisions as a provider — “not just as a nurse following orders.”

The biggest benefit in this “scary, unknown situation” is being a strong clinician, Balderas said. Her ability to quickly assess patients is especially vital amid the coronavirus pandemic, where symptoms progress quickly.

In the cancer treatment center, nurse practitioners have been forced to decide on a daily basis which patients should come in for treatment, and which patients can wait because of the risks posed by COVID-19, she said. They triage patients - assigning degrees of urgency to each patient to decide the order of who gets treatment. Then they call the patients to explain why they should or should not come in.

Those who do need treatments are screened for symptoms. If they are cleared for chemotherapy, the patients are not allowed to have visitors, guests or family, Balderas said. Any patients who come to the treatment center with symptoms are evaluated outside of the building to further mitigate risks for patients inside.

“The patients are already stressed out about their cancer, and now they have to worry about coronavirus on top of it,” she said. “I feel like we’re pivotal in supporting them because now they don’t have anyone, they have to do it alone…and that’s really tough for them.”

The additional stress is also hard on patients’ families, “especially husbands and wives,” because they are used to coming to every appointment, she said. Now they are stuck waiting in their cars or dropping the patients off. Balderas tries to call every spouse to let them know how their partner did in treatment and relay any new information to them.

“Patients are definitely more emotional since coronavirus started. They’re terrified. They’re terrified to come get their chemo, and they’re terrified to get exposed to the virus,” Balderas said. “We handle it with lots of reassurance and lots of close contact with them. I let them know they’re not bothering me, and I want to hear from them. I think it gives them a sense of comfort, knowing that someone cares for them.”

The coronavirus has been added stress for healthcare professionals like Balderas, too. There is the worry of contracting the virus and exposing her family to it, as well as gauging what patients need to hear. While she is strong at work and in front of patients, Balderas said there has been a few times she has sat in her car and cried.

However, she said she has seen the tragedy surrounding the coronavirus bring people together in her department. One of the silver linings of is that the stay-at-home order has allowed her to spend more time with her husband and daughter. Balderas destresses by “venting” with her husband, a paramedic, taking walks with her family in her neighborhood on Naples Island, and taking their ski boat out onto the water in Alamitos Bay to watch the sunset.

“On any given night now it’s my dad, my husband, myself and my daughter. It’s brought my family a little bit closer,” she said. “It’s forced us to take a deep breath and slow down.”

This is one in an occasional series where CSULB healthcare professionals share their experiences from the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read more

Nurse Monique Wood encounters a range of emotions in her daily fight against coronavirus